Urban Alienation and the Price of Truth

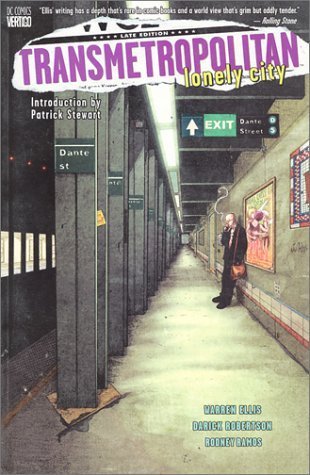

Warren Ellis’s Transmetropolitan, Vol. 5: Lonely City is an evocative meditation on urban alienation, journalistic integrity, and the relentless machinations of power. By this installment in the series, Spider Jerusalem—Ellis’s anarchic, truth-seeking gonzo journalist—is both a hunted man and a moral crusader, embroiled in a personal war against a political machine that thrives on deceit. More than just a cyberpunk graphic novel, Lonely City is a piercing critique of modern dystopian realities wrapped in the frenetic, neon-lit grime of a near-future metropolis.

Ellis’s vision of The City, in its sprawling and surreal decadence, is as much a character as Jerusalem himself. This volume isolates its protagonist in a way that magnifies his essential solitude. Though previously surrounded by his devoted “filthy assistants” and driven by the sheer momentum of uncovering governmental corruption, Spider now finds himself adrift—his relationships fraying, his notoriety endangering those around him, and his cause seeming, at times, hopeless. Yet it is in this near-total exile that the novel sharpens its philosophical inquiry: what happens when the crusader for truth loses faith in his audience?

Thematically, Lonely City channels the same existential concerns as the works of Jean-Paul Sartre or Hunter S. Thompson, merging the angst of absurdity with the rage of investigative journalism. The title itself is a loaded phrase—both a descriptor of the metropolis Spider loathes and an internalized state of being. Ellis’s narrative technique emphasizes fragmentation, presenting the reader with overlapping perspectives, distorted media broadcasts, and Spider’s own increasingly unhinged diatribes. This serves to place us in the disorienting swirl of a media-saturated society that prioritizes spectacle over substance.

Darick Robertson’s artwork remains integral to the storytelling, offering a meticulous tapestry of grotesquerie and satire. Every panel is dense with hyperbolic consumerism, mechanical excess, and the raw filth of urban living. In Lonely City, this visual chaos becomes suffocating, mirroring Spider’s own growing sense of claustrophobia and despair. Robertson’s ability to contrast extreme caricature with moments of haunting intimacy—such as Spider’s solitary moments of introspection—adds emotional weight to the book’s sociopolitical critique.

What elevates Lonely City beyond its cyberpunk trappings is its unflinching look at the psychology of alienation. Spider Jerusalem, though wrapped in layers of bravado, cynicism, and manic energy, is an archetype of the weary prophet—a Jeremiah figure shouting into the void, uncertain whether he’s making a difference. By this volume, his battle is no longer just against corrupt politicians but against apathy itself, a force more insidious than outright tyranny.

In Transmetropolitan, Vol. 5: Lonely City, Ellis doesn’t just tell another chapter in Spider’s story; he forces the reader to confront their own complicity in a world where truth is often drowned in noise. The result is both exhilarating and unnerving—a work that speaks as much to our current reality as it does to the feverish dystopia it depicts.

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.