Neil Gaiman’s The Doll’s House, the second volume in his seminal Sandman series, offers a breathtaking deepening of the mythological architecture introduced in Preludes & Nocturnes. Where the first volume was concerned with Dream’s restitution of his artifacts and identity, The Doll’s House shifts focus to explore the lives intertwined by the vast, indifferent movements of the Endless — beings who are less gods than metaphysical forces incarnate.

Gaiman is often praised for his deft blending of the mythic and the mundane, but The Doll’s House signals an evolution in his method. Here, the mythological is not simply layered atop the real; it is embedded within it, a parasitic symbiosis that suggests not only that dreams and stories shape human lives but that they exert a sovereign tyranny over them.

The narrative follows Rose Walker, a seemingly ordinary young woman who, unbeknownst to herself, becomes a “dream vortex” — a human capable of collapsing the barriers between individual dreamers’ minds. Rose’s odyssey into the dreamscape and through her own troubled family history operates both as plot and parable: the vortex threatens to destroy the Dreaming, yet Rose’s humanity demands recognition beyond the mechanistic function Dream assigns to her.

One of the most striking achievements of this volume is Gaiman’s portrayal of horror, not as a cheap affect but as an existential atmosphere. The “Cereal Convention” — a grotesque gathering of serial killers — stands as one of the most darkly comic and chilling set-pieces in graphic literature. Through these sequences, Gaiman interrogates the moral nihilism lurking beneath American individualism, where dreams curdle into nightmares of dominance and violence.

Moreover, The Doll’s House is a sophisticated meditation on identity and fragmentation. The dislocated characters — the disintegrating Unity Kinkaid, the monstrous Corinthian, the dysfunctional residents of Hal’s boarding house — are all figures of divided selfhood, reinforcing the thematic throughline that dreams, far from being fantasies of unity, often reveal the fracturing of the soul.

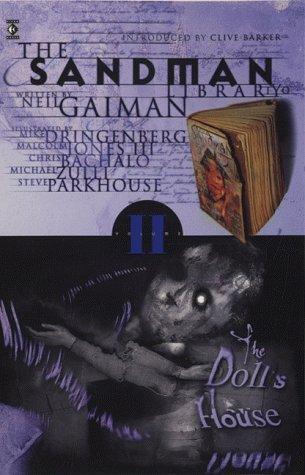

Artistically, Mike Dringenberg, Malcolm Jones III, and others evolve the visual grammar of the series. Their expressive, often grotesque renderings mirror the text’s constant oscillation between the beautiful and the horrific. Particularly notable is the surreal elasticity of the Dreaming itself, where panels lose their rigid boundaries, visually embodying the collapse of logical frameworks within dream logic.

In The Doll’s House, Gaiman moves from a brilliant pastiche artist to an architect of a new mythology — one that dares to ask what becomes of humanity when its dreams are not sources of aspiration, but forces of entropy and dissolution. His work here is not merely comic fantasy; it is a serious, layered meditation on the narratives that construct and unravel the human experience.

The Doll’s House secures The Sandman not only as a landmark in the evolution of graphic storytelling but also as a critical text in the postmodern literary canon — a gothic song of innocence lost and identities scattered like sand across the wide and shifting shores of dream.

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.