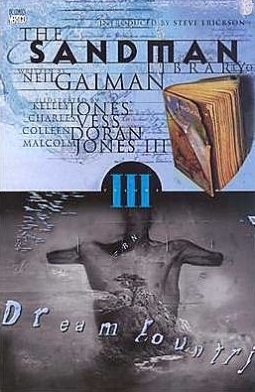

In Dream Country, the third volume of Neil Gaiman’s seminal series The Sandman, the author continues his radical reimagining of the graphic novel form, weaving a tapestry where myth, memory, and mortality are stitched together by the delicate — and often merciless — hands of Dream himself, Morpheus.

Consisting of four standalone yet thematically interwoven tales, Dream Country demonstrates Gaiman’s profound understanding of story not merely as entertainment but as existential infrastructure. Each narrative — from the tragic “Calliope” to the haunting “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” — treats storytelling as an act of both imprisonment and liberation, echoing motifs from Shakespeare, Greek mythology, and the bruised human heart.

“Calliope” is perhaps the most devastating, where the theft and exploitation of a muse lays bare the violence inherent in the creative process when it is yoked to selfish ambition. Gaiman uses the mythological to reveal brutal contemporary truths about ownership, consent, and the commodification of inspiration. The tragedy is not only Calliope’s but the writer’s as well — a cautionary tale about the ethical costs of “success.”

“A Dream of a Thousand Cats,” in contrast, plays with scale and perception, offering a parable on collective belief. Through the elegant, shifting artwork of Kelley Jones and Malcolm Jones III, Gaiman stages a subversion of anthropocentric reality itself. Here, dreams are the hidden engines of history, and consciousness is not a human monopoly but a shared, fluid inheritance.

“The Sandman” reaches a literary zenith in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” where Shakespeare’s troupe performs for the very fae creatures their play immortalizes. It is a story within a story, a dream within a dream — a brilliant metatextual commentary on the price of artistic immortality. Gaiman’s depiction of Shakespeare is empathetic but unflinching: genius as a burden, a pact, even a kind of haunting. This installment earned the World Fantasy Award for Best Short Fiction, a rare and justified recognition for a comic book at the time, signaling The Sandman‘s ascendancy into the literary canon.

Finally, “Facade” offers a quiet, mournful epilogue to the volume, focusing on Element Girl (Urania Blackwell), a forgotten hero longing for death. Here, Gaiman resists the glamorization of superpowers, suggesting instead that transformation can be a trap — a distortion of identity rather than an enhancement. Death, portrayed with luminous tenderness by artist Colleen Doran, is the only true friend.

Throughout Dream Country, Gaiman’s prose walks a razor’s edge between poetry and nihilism, buoyed by a rotating cast of artists who, though stylistically distinct, maintain a unified visual lexicon of shadows, dreams, and dissolving boundaries. The volume reveals Gaiman’s fascination with the “permeable membrane” between reality and imagination — a theme that feels both ancient and urgently modern in an era beset by contested narratives.

If the early volumes of The Sandman introduced readers to the idea that stories could be darker, stranger, and richer than conventional fantasy dared to imagine, Dream Country is the volume where Gaiman fully claims his mantle as a mythopoet of the modern age. His stories do not merely entertain; they interrogate, unsettle, and ultimately re-enchant.

In Dream Country, dreams are not escapes — they are the furnaces in which the raw ore of existence is melted and reforged. Gaiman’s achievement is to show that to dream is not to flee reality, but to remake it, word by delicate word, panel by haunted panel.

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.