A Tapestry of Dreams and Nightmares

In Abarat, Clive Barker crafts not merely a novel but a sprawling, mythopoeic world — a fantastical cartography where each island represents an hour of the day and night. At once a young adult epic and a profound meditation on time, creativity, and identity, Abarat transcends its genre conventions through Barker’s singular imaginative force.

The story follows Candy Quackenbush, an ordinary girl from Chickentown, Minnesota, whose longing for escape propels her into the archipelagic world of the Abarat. On the surface, Candy’s journey is a familiar Bildungsroman structure: a disenfranchised youth thrust into an extraordinary setting. Yet Barker complicates this trope by suffusing his heroine with a preternatural affinity for the otherworld, suggesting a deeper, almost metaphysical kinship that challenges notions of selfhood and predestination.

Barker’s prose in Abarat is rich, baroque, and at times overwhelming — a deliberate stylistic choice that mirrors the chaotic, protean nature of the world he conjures. The book is laden with the grotesque and the sublime, often in the same paragraph. His lush descriptions of monstrous beings and bizarre landscapes read like illuminated marginalia sprung to feverish life. This is no sterile, sanitized fantasy: Barker embraces the disturbing alongside the wondrous, insisting that the two are intertwined.

The novel’s structure, fragmentary and often episodic, mirrors the workings of a dream. Readers are cast adrift across islands such as Ninnyhammer, Pyon, and Gorgossium, encountering an ever-expanding bestiary of creatures, each more phantasmagoric than the last. This episodic rhythm may frustrate those seeking a tightly plotted narrative arc, but it rewards readers willing to surrender to its rhythms, much like voyagers surrendering to the tides.

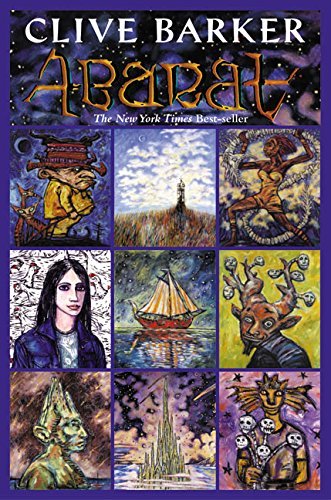

Particularly striking is Barker’s painterly imagination — unsurprising, given that Abarat was conceived alongside hundreds of vivid oil paintings, which serve as a visual counterpoint to the text. These images are not mere illustrations but integral components of the storytelling, each a portal deeper into Barker’s singular cosmology. His method evokes Blakean precedents: Abarat feels, at times, like a modern-day Songs of Innocence and of Experience, a dialogue between wonder and corruption.

Beneath the fantastical veneer, Abarat explores profound philosophical themes. Time is not simply a background motif but a character itself, mutable and alive. Candy’s growing awareness of her own multidimensional existence invites existential questions: Are we singular selves, or amalgams of all the lives we might have lived? This interrogation of identity aligns Barker with writers like Ursula K. Le Guin and Philip Pullman, yet his approach remains darker, more visceral.

Critically, Abarat refuses easy binaries of good and evil. Even its villain, the chilling Christopher Carrion, is rendered with complexity and tragic undertones, suggesting that monstrosity is often born of woundedness rather than pure malevolence. Barker’s moral universe is one where beauty is fragile, horror is intimate, and redemption is possible but never guaranteed.

Abarat is a triumph of world-building and visionary storytelling — a novel that challenges, disorients, and ultimately enriches. It demands a reader who is willing to be unsettled, to be awed, and to navigate the murky waters between nightmare and dream. Barker has given us not merely a story, but an entire mythology waiting to be lived in, feared, and loved.

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.