Ray Hemachandra’s 500 Vases: Contemporary Explorations of a Timeless Form situates the humble vase at the intersection of functional craft and high art. By juxtaposing a broad array of contemporary practitioners—from established maestros to emerging voices—Hemachandra underscores the vase’s enduring capacity to inspire innovation. As a reference work, it collects photographic documentation of five hundred distinct forms alongside concise artist statements and contextual essays. Yet it is more than a mere catalog; through its curation, the book posits the vase as both vessel and vantage point, revealing how a seemingly simple object can register shifting aesthetic values, cultural narratives, and technical breakthroughs in the twenty-first century.

Structure and Organization

The volume unfolds in three principal sections: an introductory essay that maps the historical and conceptual lineage of the vase; a core gallery of five hundred entries; and a concluding segment of thematic reflections. In the introductory essay, Hemachandra surveys everything from ancient Han dynasty funerary vessels to mid-century Modernist reinterpretations, thereby framing the vase as a “timeless container” whose genealogy extends across civilizational boundaries. This scholarly prologue, informed by art-historical precedent, immediately orients the reader to perceive each featured work not in isolation but as a node in a larger, diachronic conversation.

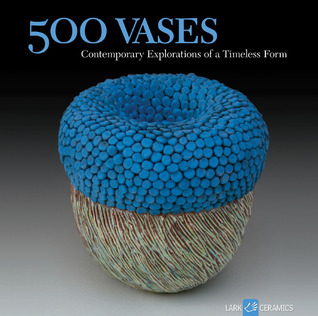

The gallery section dominates the book’s visual field. Organized alphabetically by artist surname, each vase is rendered in a full-page photograph—often against a neutral background so that materiality (clay body, glaze nuance, surface texture) takes prime focus. Opposite each photograph, a succinct artist statement provides insight into process, influence, or conceptual intent. This page-to-page rhythm—image on one side, text on the facing page—allows for contemplative viewing, encouraging the reader to linger on subtleties of color gradation, silhouette, or patterning before drilling down to the maker’s words.

Finally, in what might initially appear a prosaic afterword, Hemachandra offers three short thematic essays—“Form and Function,” “Narrative and Symbol,” and “Innovation in Material”—each drawing connections across the 500 vases. These reflections do more than summarize; they synthesize recurring motifs such as the resurgence of wheel-thrown vessel forms, the prevalence of narrative imagery (mythic or autobiographical), and the emergence of hybrid techniques (for instance, combining digital 3D printing with slip-casting). In doing so, Hemachandra transforms what could have been a static compendium into a living archive of contemporary ceramic discourse.

Formal and Aesthetic Considerations

Assessing a predominantly visual tome, one recognizes how Hemachandra’s prose functions with the precision of ekphrasis. The introductory essay models this approach by describing early ceramic prototypes—Minoan amphorae or Song dynasty porcelains—with the same acute attention to rhetorical form that a critic might reserve for a canonical poem. When he writes of “the thin shoulders of a Yi Xing vase” or “the rhythmic undulations of a hammered copper glaze,” the language operates as both didactic description and poetic meditation. Thus, the text becomes a conduit, coaxing the reader to see beyond utilitarian function into realms of symbolic resonance.

Moreover, the book’s design choices—ample white space, deliberate sequencing of tranquil, symmetrical forms alongside more exuberant or gestural works—mirror Hemachandra’s argument that the vase, in its ideal state, balances serenity and surprise. A minimalist stoneware pot by one artist may directly face a vigorously patterned porcelain vessel by another. This juxtaposition creates an implicit dialogue in which silence and spectacle coexist on the same visual plane. Hemachandra’s curation trusts the reader to decode this dialogue: he refrains from didactic commentary in the gallery pages, allowing juxtaposition itself to teach.

Cultural and Philosophical Dimensions

Beyond formal analysis, Hemachandra invites readers to contemplate the vase’s status as metaphor. In his “Narrative and Symbol” essay, he observes that many contemporary ceramists use the vase as a site for personal or collective storytelling: imagine a wheel-thrown vessel in which sgraffito reveals layered topographies evoking diaspora or displacement, or a slab-built form whose irregular rim speaks to environmental disruption. Here, he effectively recuperates the vase from mere decorative objecthood, positioning it as a medium for social commentary. Hemachandra references works where fissures in the clay become “cracks in collective memory,” suggesting that the vases trace not only physical contours but also the fissures of identity and loss.

Furthermore, Hemachandra attends to questions of material ethics. In the concluding essay on innovation, he profiles artists who repurpose industrial by-products (fly ash, slag) in place of virgin clays, thereby gesturing toward an eco-ethical imperative. He introduces, for example, a series of earthenware vessels glazed with recycled glass frit, remarking that “the vessel, once a repository for life-sustaining water, now doubles as a vessel for critical commentary on sustainability.” This framing pushes the reader to see the vase not only as an aesthetic object but as a site where environmental, political, and ethical concerns converge.

Critical Appraisal

One might critique 500 Vases on grounds of selectivity: with a global field comprising thousands of ceramicists, the choice of 500 inevitably foregrounds certain regions and traditions over others. Hemachandra does include a disclaimer noting that a single volume cannot encompass every cultural vernacular, but readers seeking deeper representation of, say, indigenous North American or Sub-Saharan African practices may find those traditions underrepresented. Additionally, while the alphabetical organization affords ease of reference, it diminishes opportunities for exploring genealogies by region, technique, or conceptual affinity. A thematic or chronological grouping—while less straightforward—could have further deepened the dialogic possibilities between works.

Nevertheless, the book’s strengths outweigh these limitations. Hemachandra’s lucid prose—at once poetic and precise—anchors the volume’s grand visual sweep in intellectual rigor. By refraining from overly prescriptive interpretation in the gallery itself, he preserves space for readers to engage directly with each form, trusting in the viewer’s capacity for visual literacy. His concluding essays then knit together these encounters into broader critical narratives, ensuring that the reader emerges not merely with an inventory of beautiful objects, but with a nuanced understanding of why the vase, even in 2025, remains an open-ended forum for artistic inquiry.

500 Vases: Contemporary Explorations of a Timeless Form succeeds as both scholarly repository and aesthetic manifesto. Hemachandra’s dual role as curator and critic allows him to traverse categories of craft, design, and fine art with confidence, offering readers a panoramic vista of contemporary ceramic practice while never losing sight of the vase’s deeper anthropological, ecological, and formal resonances. For ceramics scholars, practicing artists, and even armchair aesthetes, this volume provides a compelling entry point into the ever-evolving dialogue about how simple forms can articulate complex human concerns. In treating the vase as a “timeless form,” Hemachandra reminds us that, across epochs, the impulse to shape clay into something that holds and protects—be it water, flowers, spiritual offerings, or memory itself—remains a profoundly human act.

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.