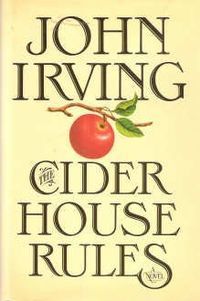

John Irving’s The Cider House Rules (1985) is at once a sprawling coming‑of‑age narrative, a moral fable, and a wry social satire, woven together by the author’s trademark blend of dark humor and tender empathy. At its heart lies the orphan Homer Wells, whose journey from the murky underside of Dr. Wilbur Larch’s orphanage to the orderly chaos of the Maine apple country poses profound questions about choice, duty, and the arbitrary lines drawn by law and tradition.

Narrative Structure and Voice

Irving divides his novel into three distinct phases—Homer’s childhood at St. Cloud’s Orphanage, his sojourn under the tutelage of Larch, and his reluctant assumption of a house‑doctor’s mantle at the cider farm. This tripartite structure mirrors the bildungsroman tradition yet subverts its predictability by threading in episodes of farcical exaggeration: the fisheries, the clandestine abortions, the eccentric Swedish apple pickers. Goldbergian in its scope, the novel alternates deadpan irony with moments of genuine pathos, as though Homer’s pragmatic narration were forever challenged by the absurdity of human cruelty and kindness.

Themes of Morality and Choice

Central to the text is the fraught question of reproductive ethics: Dr. Larch’s covert abortion practice in defiance of deep‑seated legal and religious proscriptions. Homer’s initial moral ambivalence—shaped by both Larch’s pragmatic compassion and the orphanage’s lore—evolves into an ethical imperative that compels him to weigh individual autonomy against communal taboo. Irving uses the orchards as a leitmotif of fecundity and sacrifice: apples ripen only by shedding their blossoms, and yet those blossoms, once gone, cannot be reclaimed—much like the decisions faced by the women who come to St. Cloud’s.

Characterization and Interpersonal Dynamics

Homer Wells emerges as the novel’s moral fulcrum: he is both a self‑styled Locksmith—patching the world’s wounds—and a man incapable of the simple act of refusal. His mentor, Dr. Wilbur Larch, is one of Irving’s richest creations: a physician with an encyclopedic knowledge of orphans’ names, a voracious intellect, and a devil‑may‑care generosity that masks a profound loneliness. The supporting cast—Melony, Candy, Wally Worthington—are sketched with caricatural strokes yet given emotional depth in their struggles with love, loss, and the failures of institutions.

Style and Symbolism

Irving’s prose is at once limpid and labyrinthine: sentences swell with parenthetical asides and anecdotal digressions, only to snap back to a crystalline clarity of moral inquiry. The cider house itself, with its “rules” written on oilcloth sheets, stands as a metaphor for the codified norms that govern community life—norms that Homer must reinterpret through his own lived experience. In scenes of harvest, Irving’s descriptive gifts flower: the heady scent of crushed apples is almost palpable, transforming the farm into a character in its own right, a locus where nature’s cycles mirror human rites of passage.

The richness of The Cider House Rules lies not merely in its narrative heft but in its unflinching engagement with the ethical dilemmas of its era—and ours. Irving does not offer pat solutions; rather, he invites us to reckon with the complexity of compassion, the weight of choice, and the necessity of breaking “the rules” when they injure. As a literary scholar might observe, the novel’s lasting power stems from its ability to fuse grand moral questions with the particularities of place and personality, reminding us that every act of mercy is, in turn, an act of rebellion.

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.