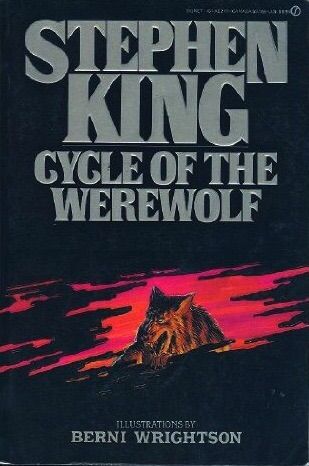

Stephen King’s Cycle of the Werewolf, first published in 1983 with illustrations by Bernie Wrightson, occupies a curious place in his oeuvre. At just over 40 pages, it marries the concise structure of a novella to King’s characteristic attention to small-town Americana. Though compact, its twelve-month chronology and interplay of horror, folklore, and social portraiture reward close scrutiny.

Summary

Set in the insular Maine village of Tarker’s Mills, Cycle of the Werewolf unfolds month by month, each installment corresponding to a lunar phase and its toll of lycanthropic violence. Beginning in January with a chilling prologue at a New Year’s party and culminating the following December in an act of grim resolution, the novella charts how a rural community confronts—and ultimately confronts head-on—its own mythic terror. The story’s sparse cast includes the innocent young Marty Coslaw and his deeply protective parents, the skeptical local constable, and the shamanistic outsider Reverend Lowe, whose hidden knowledge proves pivotal.

Narrative Structure and Pacing

King’s choice to segment the narrative into twelve discrete chapters not only mirrors the calendar year but also amplifies suspense through methodical pacing. By allotting one lunar cycle per chapter, King transforms what could have been a sprawling tale into a distilled series of atmospheric vignettes. This structural economy echoes classical literary calendars—such as Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales—while simultaneously creating a mounting sense of dread: by the time April’s thaw brings the werewolf into vivid daylight, readers are primed by the accumulated tension of prior months.

Themes and Subtext

At its core, Cycle of the Werewolf is less about the supernatural than it is about collective fear and the failings of communal institutions. Tarker’s Mills, with its genteel facade, conceals undercurrents of small-town prejudice and moral complacency. King deftly portrays how the townsfolk’s initial amusement at rumors gives way to wrapped-in-silence gossip, and ultimately to terror-driven scapegoating. The werewolf itself functions as a cipher for nature’s untamed force and for the suppressed darkness lurking within every social order. Moreover, King subtly interrogates the mythic allure of folklore: the villagers’ reliance on Reverend Lowe’s shamanic rites suggests a vacillation between modern rationalism and ancestral superstition.

Characterization and Point of View

Though the narrative perspective shifts subtly—from the omniscient descriptions of townsfolk to the intimate anguish of the Coslaws—King restricts deep interiority to heighten the novella’s folkloric tone. Marty’s chilling brush with the werewolf’s gaze in April provides the emotional anchor, transforming the story from an abstract horror sequence into a personal coming-of-age ordeal. The absence of overextended character backstories is a deliberate choice: by preserving a degree of narrative distance, King evokes the feeling of an oral tale, recounted by the flickering light of a hearth yet tinged with personal loss.

Style and Imagery

Bernie Wrightson’s stark black-and-white illustrations frame each chapter, reinforcing the novella’s interplay of shadow and revelation. King’s prose here is taut and evocative, favoring sharp, sensory details over the expansive digressions of works like It or The Stand. His descriptions of the werewolf—its shifting silhouette on winter-white snow, the glint of moonlight on its fang—redeem the novella from predictability. Moreover, King leverages the Maine winter landscape as more than mere setting: its oppressive cold, the isolating drift of snow, and the pale winter sun become characters in their own right, complicit in the villagers’ slow suffocation.

Conclusion

Cycle of the Werewolf stands as a masterclass in narrative economy. Within its slender frame, Stephen King charts the anatomy of fear, scrutinizes communal indifference, and revives archaic myth in a modern guise. While some may dismiss it as a mere illustrated gimmick, readers attuned to its structural rigors and thematic undercurrents will find in it a concentrated distillation of King’s broader preoccupations—small-town America, the porous boundary between mankind and monstrosity, and the power of folklore to illuminate, and to terrify. In this cycle, the horror is not only in the beast that lurks under moonlight, but in the reflection it casts on ourselves.

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.