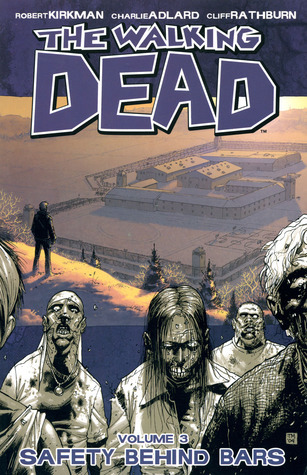

Volume 3 of The Walking Dead marks a tonal pivot in Kirkman’s ongoing meditation on catastrophe: the terror of the undead remains the engine, but the narrative energy increasingly diverts into the human architectures we build to live with that terror. Where earlier volumes foregrounded immediate survival and the shock of societal collapse, Safety Behind Bars examines the fragile institutions that survivors improvise—walls, rules, hierarchies—and the psychic cost of trying to make permanence out of ruins.

Close reading — themes and technique:

Kirkman’s central conceit is deceptively simple and powerfully generative: apocalypse does not only expose the body to danger, it exposes the moral imagination. In this volume the prison (both literal and metaphorical) functions as an organizing symbol. Its heavy, rectilinear forms—cellblocks, bars, locked gates—satisfy the primal wish for enclosure and protection, yet they are also a mirror. The same structures that keep walkers out begin, in the narrative, to reveal what keeps people in: fear, memory, rivalry, and the sediment of pre-apocalypse social roles.

Kirkman is interested in authority under duress. Rick’s attempt to transform a band of traumatized strangers into a functioning polity is quietly political: it asks what kinds of leadership are effective when bureaucracy, law, and legitimacy have collapsed. The tension between pragmatic stewardship and personal desire—most famously embodied in the rivalry that has been simmering between Rick and Shane—becomes more than melodrama here. Kirkman stages leadership as a constant negotiation: who enforces rules, who interprets them, and at what moral cost? This negotiation is not resolved by cinematic heroics but by small, weary decisions that feel earned and, unsettlingly, ambiguous.

Stylistically, the volume balances blunt, spare dialogue with moments of lingering, visual silence. The comic form is used to excellent effect: panels compress time for sudden bursts of violence, and stretch it for scenes of domestic unease (sleeping children, half-repaired fences, whispered conversations). The black-and-white art accentuates the moral chiaroscuro; without color, expressions, posture, and negative space carry the emotional load. Kirkman’s scripting privileges ordinary details—shared meals, arguments over chores, a repair of a fence—which in this context take on quasi-sacramental significance. These quotidian acts are how characters attempt to stave off entropy, and the book makes the reader feel both the nobility and the futility of that effort.

Another prominent theme is the depiction of community as both balm and constraint. The prison becomes a crucible for interpersonal economies: altruism is real but transactional; trust is built slowly and taxed immediately. Kirkman resists the binary of “good survivors” vs. “bad survivors.” Instead, moral choices are contextualized, unpredictable, and often tragic. This ethical complexity elevates the work from genre horror to social fable: the monsters outside are deadly, but the narratives’ real questions concern what kinds of societies we construct when the old ones fail—and who gets to decide the terms.

On violence and pathos:

The book does not shy away from explicit, sometimes brutal violence. Yet these moments are not spectacle for their own sake; they are dramaturgical punctuation that forces the characters (and the reader) to reckon with loss as a structural condition. Kirkman’s handling of grief—its eruptions and its banality—is one of the volume’s quietly affecting strengths. Grief here is not only raw anguish but also a labor: it must be managed, deferred, ritualized if the group is to persist.

Limitations:

Viewed as serialized storytelling, some sequences can feel episodic—scenes designed first for monthly cliffhangers then stitched into volume form. A reader seeking a tightly unified novel may perceive small tonal hiccups where the pace accelerates or stalls. There is also a risk (not unique to Kirkman) that extended focus on interpersonal entropy can flirt with soap operatics: passion, jealousy, rivalries occasionally verge on the sensational. That said, these tendencies are checked by Kirkman’s consistent moral seriousness; melodrama here is often a consequence of real stakes rather than cheap plotting.

Significance and readership:

Safety Behind Bars is where The Walking Dead begins to show its ambitions beyond survival horror and into realist political allegory. It asks urgent questions—about authority, about the ethics of enclosure, about how the ordinary rituals of community become technologies of survival—and refuses simple answers. For readers interested in genre fiction that thinks, it demonstrates how the postapocalyptic tale can function as a laboratory for human behavior: stripped of institutions, what habits and values persist? Which are invented anew?

Recommended for readers who appreciate character-driven serials, moral ambiguity, and comics that use form (paneling, silence, stark art) to deepen theme. Kirkman’s volume is not comfortable reading—nor is it meant to be—but it is thoughtful in the way that makes discomfort productive: it forces reflection about the structures we prize when we imagine ourselves safe behind any kind of wall.

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.