Robert Kirkman’s The Walking Dead, Vol. 13: Too Far Gone is a pivotal moment in the long arc of his survival epic, one that not only redefines the psychological terrain of his characters but also interrogates the very notion of civilization itself. After the harrowing violence of previous volumes, the survivors are granted what appears to be a reprieve: the Alexandria Safe-Zone, a walled community promising security, domesticity, and a simulacrum of normal life. Yet, as the title suggests, the central question is whether Rick and his group are “too far gone” to re-enter the world of civility after so much trauma and brutality.

Kirkman employs the Alexandria arc as a narrative crucible, contrasting the hardened survivors with those who have managed to maintain vestiges of pre-apocalyptic morality. In doing so, he dramatizes the tension between two modes of existence: the feral pragmatism forged in catastrophe and the fragile social contract of community life. Rick’s arc, in particular, becomes emblematic of this conflict. His paranoia, vigilance, and authoritarian instincts—traits necessary for survival in the wilderness—become sources of unease in a structured society. The volume interrogates whether leadership grounded in perpetual suspicion can ever reconcile with the demands of peace.

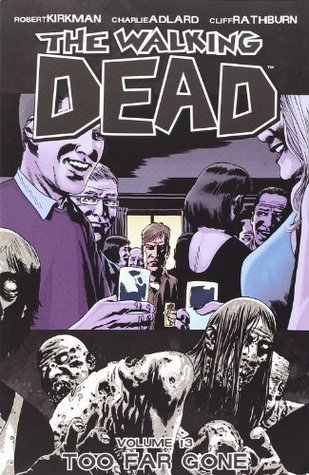

Artist Charlie Adlard’s stark black-and-white visuals accentuate this thematic tension. The absence of colour allows for a heightened focus on facial expressions, body language, and the symbolic weight of architectural spaces: the high walls of Alexandria, the domestic interiors, and the watchtowers all become visual metaphors for both protection and imprisonment. The relatively quiet panels—moments of dinner conversation, guarded smiles, tentative gestures—create an uncanny dissonance, as if peace itself is haunted. Violence, when it erupts, feels both inevitable and disruptive, a reminder that the apocalypse lingers not just outside the walls but within the survivors themselves.

From a literary standpoint, Too Far Gone explores the fragility of reintegration after trauma. The survivors’ difficulty in relinquishing their survivalist mentality echoes post-war literature in which soldiers struggle to return to civilian life. In this sense, Kirkman situates his narrative within a broader cultural meditation on the psychological costs of violence. The title becomes a refrain: can one return to normalcy after having lived “too far gone,” or does the apocalypse permanently rewrite the human psyche?

Ultimately, this volume is less about zombies than about the haunting endurance of human memory and mistrust. Kirkman refuses to offer simple resolutions; instead, he allows his characters to stumble toward an uneasy equilibrium, gesturing to the broader thesis of the series: survival is not only about enduring the external apocalypse but about confronting the internal transformations it demands. In Too Far Gone, the real horror is not the collapse of civilization, but the realization that one may no longer belong to it.

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.