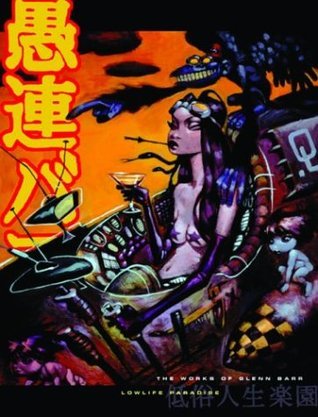

Lowlife Paradise: The Works of Glenn Barr arrives, for readers and viewers alike, as more than a catalogue raisonné or a retrospective: it is a focused attempt to translate a restless, pictorial imagination into the language of the book. Glenn Barr’s work—at once cartoonish and baroque, playful and implacably strange—resists tidy taxonomies; this volume, by taking his visual idioms seriously, offers a vantage point that lets those idioms disclose their contradictions and ambitions.

Visual grammar and recurring motifs

What makes Barr’s images linger is their doubleness. At first glance they read as exuberant caricature: exaggerated heads and limbs, bubble-like bodies, and a surface delight in pattern and repetition. But look longer and a darker economy appears. Figures that flirt with the comic slide toward the grotesque; bright colours sit beside a corrosive sense of depletion; gestures that announce vitality also register fatigue. Barr’s pictorial grammar—bold contours, flattened spatial planes, rhythmic ornamentation—borrows from comic strips, folk signage, and mid-century commercial illustration, then refashions those sources into something closer to an incantation than an homage.

The book does well to let the images speak. Reproductions emphasize the tactile—ink, brush, collage—and often preserve the hand-made corrections and scumbles that are Barr’s signatures. This is crucial: much of Barr’s effect depends on the tension between the mechanical clarity of cartoon line and the messy exuberance of painterly intervention. The artist’s repeated use of motifs—animalized humans, hybrid objects, and scenes of ambiguous ritual—creates a private mythology. Rather than offering a linear narrative, these motifs accumulate, producing a mythic topology in which the banal (a soda can, a street sign) becomes a totem of estrangement.

Themes and currents: humour, menace, and Americana

A literary sensibility is useful here because Barr’s images function like short fables—compressed narratives in which the punchline is never purely comic. Humour in his work is often a device for moral or existential unease rather than mere levity. There is a persistent Americana in the iconography: neon-styled typography, fragmented advertising language, and roadside ephemera, all filtered through a sensibility that both loves and warps its sources. This ambivalence—an affection that includes corrosion—is one of the volume’s richest veins.

Another constant is physiological excess. Faces balloon; limbs flex beyond natural proportion; bodies become landscapes. Such formal decisions register a philosophical concern: the limits of representation, the instability of identity, and the porous boundary between human and thing. Barr’s compositions stage a negotiation between the cheerful surfaces of popular visual culture and the subterranean sensations that culture often masks—loneliness, alienation, and the desire for escape.

The book as object and the curator’s choices

As an object, Lowlife Paradise treats its subject with respect. The sequencing—whether chronological, thematic, or hybrid—matters less here than the editors’ decision to allow visual resonances to govern the reader’s journey. Interleaving large plates with smaller studies creates rhythms that mirror Barr’s own oscillations between elaborated canvases and quick sketches. The scholarly apparatus—if present—balances provenance, technical notes, and interpretation without privileging any single reading.

Where the volume is strongest is in the attention to materiality: high-quality plates, generous margins, and reproductions that retain the grain of paper and the bleed of ink. These choices acknowledge that Barr’s work is not purely about motif but about the act of making—the scratches, the erasures, the accidental marks that become expressive. For scholars interested in process, these visual clarities are indispensable.

Critical considerations

No monograph is without lacunae. Readers seeking exhaustive contextualization—extensive archival essays, detailed biographical excavation, or sustained comparison with contemporaneous movements—may feel the book only sketches the periphery. The risk with any monographic treatment of an artist like Barr is twofold: either to over-domesticate a mercurial practice with theoretical scaffolding, or to leave the work under-theorized. Lowlife Paradise generally errs on the side of restraint, privileging images over argument. That is defendable aesthetically, but it means that some interpretive questions (about Barr’s influences, his place in successive “lowbrow” or pop-surreal currents, or his relationship to contemporaneous social conditions) remain provocatively open.

Another small reservation concerns editorial voice. A few essays—when they appear—move too quickly from observation to broad cultural claim. A more careful calibration between close visual analysis and cultural synthesis would strengthen the book’s value for specialists.

Value and audience

Lowlife Paradise is a thoughtful, beautifully produced airing of Glenn Barr’s singular vision. It will serve both as an accessible introduction for newcomers and as a rich visual resource for collectors, curators, and scholars interested in the porous boundaries between popular imagery and fine art. Most importantly, the book respects the primary thing: Barr’s pictures. By foregrounding materiality and allowing motifs to accumulate, it mirrors the artist’s own methods—associative, recursive, and stubbornly imaginative.

For anyone who wants to understand how late-20th-century visual culture can be turned, by a single voice, into a private cosmology, this volume is a necessary stop. It does not answer every question about Barr; instead, it deepens them—inviting readers back into the images, where new meanings continue to ripple beneath their bright, uncanny surfaces.

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.