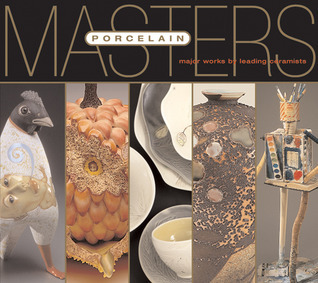

Porcelain is the element of modern ceramics that most insistently asks to be read: thin as a page, luminous as lamp-glass, it carries with it histories of trade, empire, ritual and domestic intimacy. Masters: Porcelain is, at its best, a sustained act of close-looking — not a how-to manual but a catalogue raisonné of presence. Lark Press, working in the register it has long cultivated (beautifully produced, photography-forward, companionable to makers), assembles here a sequence of objects that together stage an argument: that porcelain remains a site where technical virtuosity and conceptual poise can meet in the same gesture.

The volume’s most persuasive achievement is aesthetic: the photographs and reproductions convert three-dimensional fragility into an almost literary texture. Plates arrest the eye — a bowl’s rim folded like a page turned, a glaze’s micro-crackle read as a network of punctuation — and the editorial design lets these images breathe. Images are not mere documentation but interpretive acts; the camera’s intimacy with surface encourages the reader to “read” glaze, form and repair as one would a poem’s enjambment. In this sense the book treats porcelain as language: minimal forms become sentences, each mark of the potter a comma or caesura.

Interleaved with the visual material are essays and artist statements that perform a useful balancing act. The more reflective texts frequently do the work of historicizing and theorizing without lapsing into the jargon that often clutters arts writing. Where technical descriptions are required — clay bodies, firing temperatures, glaze recipes — they are offered as practical annotations rather than fetishized secrets, which makes the book useful to practitioners without losing a general reader. When an artist speaks about process, one senses a quiet pedagogy: confession and demonstration braided together so technique is shown as ethical choice as much as skill.

If the book has a curatorial stance, it is one of restraint. The selections favour works in which restraint is itself an aesthetic proposition: pared-down profiles, subtle surface violences (a single, intentional nick; a repaired crack that becomes a graphic line), and an emphasis on the liminal — edge, translucence, and negative space. This is where the volume’s criticism becomes implicit: it valourizes reduction and refinement, privileging gestures that make porcelain’s material vocabulary legible. The result is a clear editorial voice, but also a blind spot: readers hoping for riotous, ornamental, or expressly vernacular deployments of porcelain may find the book’s aesthetic ordered, even conservative. That limitation is not a flaw so much as a curatorial choice; it simply circumscribes the book’s claim to comprehensiveness.

A strength worth noting is the book’s handling of continuity — the way it situates contemporary studio practice within porcelain’s longue durée. Short contextual essays and historic referents provide an undercurrent that prevents the photographs from floating free of time. The book does not attempt to rewrite ceramic history; instead it traces affinities — between Eastern and Western lineages, between functional ware and sculptural object — and thereby models how a single medium can hold multiple genealogies without collapsing them into a single narrative.

For practitioners, collectors and scholars, Masters: Porcelain performs two complementary functions. It is a field guide for sensibility — teaching nuance by example — and a catalogue of models for future experimentation. For the general reader it operates as an object lesson in attention: the book rewards slow looking and returns often to the pleasures of surface and form. It is also an object in its own right; Lark’s material care (paper choice, type, and layout) echoes the very values it documents: tactility, silence, and precision.

If one were to ask for more, it would be for a sharper engagement with social and ecological implications of contemporary studio practice — the labor politics of ceramics, or the environmental footprint of repeated firings — topics that the book touches on but does not center. Similarly, further attention to non-Western contemporary practices would broaden the volume’s geographic imagination beyond the impressive but selective chorus of “leading” makers.

Ultimately, Masters: Porcelain succeeds because it treats making as thought. It is not merely a compendium of beautiful objects; it is a reflective anthology that insists porcelain is not a passive medium but a language for articulating gestures of care, memory and restraint. For anyone who wants to learn how to see what a pot can mean, this book is an exemplary tutor.

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.