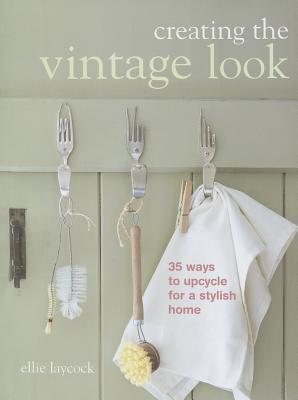

Ellie Laylock’s Creating the Vintage Look arrives as a gentle manifesto for the second life of things. Part practical handbook, part elegy for the handcrafted object, the book stages thirty-five projects that read as short essays in material culture: each one a measured argument for keeping, altering, and celebrating the past rather than erasing it. Her real subject is not merely technique, but a way of seeing — an attentiveness to the small histories and latent possibilities in worn surfaces, forgotten drawers and discarded textiles.

Structurally the book is economical and deliberate. The 35 projects function like a curated exhibition, moving through furniture revivals, textile reworking, small decorative artifacts and DIY finishes. Each entry is compact — a brief preface of intent, clear step-by-step instructions, and a visual accompanist (photography and diagrams) that keeps the reader oriented. This cadence — explanation, demonstration, and example — is a modest but effective rhetorical strategy. It democratizes skill: the author never assumes a professional background, but neither does she patronize. The tone is that of a practised teacher who trusts the learner’s sensibility.

Two thematic threads run quietly throughout the book. The first is memory as material. Repurposing is presented as storytelling: a table’s chipped varnish is not damage but evidence of use; a curtain’s sun-faded strip is narrative. These projects solicit the reader’s curiosity about provenance and invite small acts of preservation that double as design choices. The second theme is restraint. The vintage look here is not about pastiche or slavish historical replication; it is about selective intervention. A distressed paint finish, a swapped knob, an embroidered patch — these are modest gestures that allow objects to accrue new chapters without erasing their old ones.

From a craft perspective, its strengths are clarity and aesthetic sensibility. Her instructions are judiciously illustrated, and her choice of techniques privileges accessibility: sanding and waxing rather than complicated joinery, fabric dyeing and patchwork rather than full reupholstery. This makes the book especially well suited to an audience that desires immediate, visible results — homeowners, makers, and interior lovers who are impatient for transformation but cautious about technical risk.

Critically, the book’s restraint is also its limit. Readers seeking archival rigour — a deeper investigation into the histories of design moments or the provenance of vintage materials — will find Laylock’s approach appropriately light but occasionally evasive. There is also a small tension between the book’s celebration of imperfection and the polished photographs which sometimes stage wear as artifice. In a few projects the “vintage” outcome looks less like the honest patina of age and more like a curated aesthetic; the book could have benefitted from more discussion of ethics and sourcing (what to look for when reclaiming materials; when to restore rather than simulate).

Yet these are minor quibbles beside what the book achieves: an invitation to slow down and to recompose domestic life from found, repaired and reimagined parts. The author writes with a quiet persuasive authority; her projects become lessons in seeing and in intentional making. The book sits at a useful intersection — part practical manual, part aesthetic primer — and will be particularly valuable to readers who want design with conscience: stylish outcomes that foreground reuse and the relish of handiwork.

In short, Creating the Vintage Look is an encouraging, well-crafted guide for anyone who wants their home to look like a lived life rather than a showroom. It is not a definitive treatise on vintage culture, but it is an accessible, thoughtful companion for makers who wish to make less new and love what endures.

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.