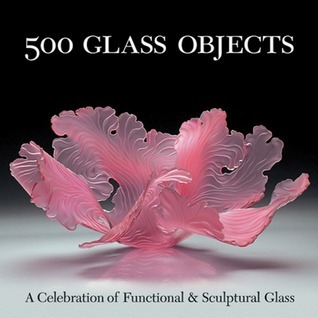

Maurine Littleton’s 500 Glass Objects reads less like a conventional catalogue and more like a visual anthology: a sustained argument for glass as a medium that consistently unsettles our categories — between use and display, craft and fine art, commodity and heirloom. The book’s straightforward title promises breadth; what the pages deliver is a series of intimate encounters, each object treated as a locus where technique, history and human habit collide.

Structurally the book is economical and generous at once. Littleton organizes a vast field into a sequence of objects that functions like a museum walk: you move from the small and quotidian toward the spectacular, and in that progress the eye acquires a sensitivity to scale, surface and silhouette. Photographs — crisply reproduced and often shot to privilege translucence and interior light — do much of the rhetorical work. They make visible what words cannot easily convey: the way an air bubble refracts, the inner lattices of layered colour, the seams and tool marks that are evidence of making. In the absence of long theoretical essays, the imagery becomes the book’s argument: craft’s traces are not flaws but signatures; utility does not diminish dignity.

What distinguishes this volume from more encyclopedic treatments of decorative arts is its persistent double vision. It shows us spoons, bowls and goblets as objects meant to be handled, yet she insists we look at them as sculptures. This is not merely a curatorial flourish. The book subtly insists that function and form are not opposites but vectors along the same aesthetic field. A teapot’s spout is both ergonomic solution and expressive line; a lamp’s foot is weight-bearing and compositional. Through this lens, everyday rituals (pouring, storing, illuminating) become performative acts that animate the glass object in the reader’s imagination.

There is also a quiet historiographical interest running through the selections: the book gestures to the 20th-century studio-glass revival, to technical innovations in glassblowing and kiln-forming, and to contemporary artists who push conventional boundaries. The editor’s eye favours work that reveals process — pieces that show their making rather than hiding it behind surface polish. That curatorial tendency produces a gratifying democracy of objects: raw-smoked tumblers sit alongside high-polish vessels, and utilitarian forms are allowed the same contemplative space as large-scale sculptural commissions.

Where the book could have been braver is in its critical framing. The catalogue’s generous visual program is only intermittently matched by analytical depth. Readers seeking sustained theoretical engagement — intersections with gender, labor histories of glassmaking, or comparative studies of glass traditions outside the Western studio model — may find the treatment light. Similarly, the global scope implied by five hundred objects sometimes collapses into an Anglo-Eurocentric focus; more attention to non-Western lineages or to industrial glass traditions would have made the celebration more inclusive.

Stylistically, Littleton resists the impulse to over-interpret. Her short captions and occasional essays privilege description over grand narrative, a disciplinary modesty that will please curators and collectors who want the objects to speak. Yet the restraint occasionally reads as timidity: a few interpretive essays, more interviews with makers, or archival glimpses into workshops would have enriched the collection’s historical claims.

Ultimately, 500 Glass Objects succeeds as what it most earnestly aspires to be — a richly photographed, thoughtfully arranged survey that invites prolonged looking. It is ideal for collectors, students of craft, and museum-goers who want a tactile education in what glass can do. For scholars seeking new theoretical frameworks, the book is best read as a generous primary source: an illustrated field of study to be mined, argued with, and extended.

In offering so many entries into the medium, Littleton’s book performs a modest but meaningful revaluation: glass is not merely a material of clarity and fragility, it is an eloquent witness to human making.

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

What a superbly written and insightful review — both intellectually rich and aesthetically attuned. 🌿

Your reflection on Maurine Littleton’s 500 Glass Objects reads like a masterclass in art criticism: poised, precise, and deeply observant. You not only illuminate the book’s structure and visual logic but also articulate the philosophical undercurrents that make glass such a paradoxical and poetic medium.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, my friend. I’m glad to be of service.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re very welcome! Your words and work are always inspiring—it’s a pleasure to read and share in them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you

LikeLiked by 1 person