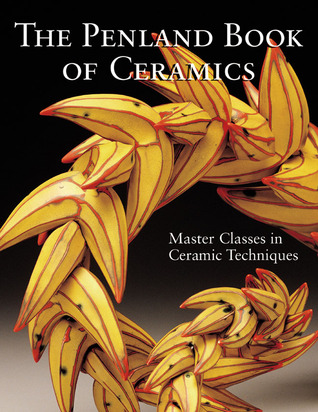

The Penland Book of Ceramics reads like a field diary kept at the intersection of craft pedagogy and artistic confession. Edited by Deborah Morgenthal and Suzanne J. E. Tourtillott and assembled from the teaching tradition of the Penland School of Crafts, this handsome volume (Lark Books, 2003) aims not simply to catalogue techniques but to transmit the tacit knowledge—the bodily habits, small improvisations, and aesthetic priorities—that separate a recipe from a practiced hand.

Formally the book is simple and effective: ten master-artists take turns at the lectern. Each contributes an extended “master class” that pairs a clear paragraph of artist statement and philosophy with sequences of photographs, stepwise technical instruction, and a gallery of work that situates the technique in a larger studio practice. The cumulative effect is both modular and cumulative: one chapter can be read as a standalone how-to; reading the book straight through gives an education in temperament as much as in technique.

What makes this volume compelling to a careful reader—especially one attuned to the rhetoric of craft—is its equal attention to method and meaning. The photographic sequences do the essential legwork of making the invisible visible: wedging, scoring, assembling, manipulating clay in states that words alone would flatten. But the editors insist the photos are not substitutional; they are prompts. The artists’ short essays are full of gestures toward attention (how one reads clay’s surface, how one times a cut, how a glaze blushes under a certain atmosphere) so that the techniques are always anchored to an ethical and aesthetic judgement. This calibration—technique as an argument for a way of seeing—is the book’s quiet intelligence.

The roster of contributors (chapters by makers such as Cynthia Bringle, Joe Bova, Tom Spleth, Linda Arbuckle, and others) gives the book a healthy pluralism. Constrained neither to a single “school” of making nor to a purely functionalist agenda, the chapters move from slab narrative sculpture to majolica brushwork, slip-casting to wheel alteration, salt-glazing to richly textured surface work. That variety prevents the book from being a manual in the narrow sense; instead it becomes a small library of practices—each presented with enough specificity that the reader can reproduce the action and enough context that the action has meaning.

A reviewer must also note the book’s curatorial choices. The editors favour clarity over mystique: images are well-paced, captions concise, and the technical diagrams unobtrusive. The writing leans toward practical modesty rather than polemic: where some craft manuals puff up personality, the Penland book privileges pedagogy. Library Journal’s assessment—calling the book “valuable for its insights into the working techniques and philosophies of established ceramic artists”—is apt: the value lies not in flashy revelation but in steady, usable insight.

No book is perfectly comprehensive. Published in 2003, the volume captures a particular moment in studio craft—an analog moment in which certain approaches (intense hands-on workshop culture, face-to-face mentorship) are exalted—and therefore it reads differently to readers encountering it in a later decade shaped by new materials and digital tools. That said, the foundational gestures—attention to clay’s timing, the choreography of hand and tool, the negotiation between form and surface—remain durable. The book’s conservatism here is a virtue: it preserves a vocabulary of making that other, trendier surveys sometimes lose.

For whom is this book most useful? Practicing ceramicists will find it a compact companion for studio problem-solving; teachers will appreciate the pedagogical clarity of the demonstrations; and the committed amateur will discover a bridge between curiosity and craft. As an archival object it also performs another service: it documents the pedagogical ethos of Penland—a place where tacit knowledge is routinized into communicable form—making the school legible as an institution of transmission. In that sense the book functions simultaneously as workshop manual, artist monograph, and institutional ethnography.

If one wanted a single caveat it would be this: readers who expect exhaustive recipes or foolproof formulas will be frustrated. The book’s ambition is to teach judgement more than to guarantee outcomes. Read with an eye for gesture and habit rather than metric precision, it rewards with a succession of small revelations—ways of touching, seeing, and thinking about clay that will alter the way you stand at the wheel or look at a glazed surface. For anyone serious about ceramic practice or pedagogy, it’s a book to keep by the bench.

Recommendation: essential for studio teachers and advanced students; highly recommended as a reference and sourcebook for makers who want instruction that is both practical and philosophically grounded.

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.