At first glance Robert Munsch’s Love You Forever presents itself as the kind of picture book that trades in the obvious—short sentences, a repeating refrain, and a domestic tableau meant to reassure a child at bedtime. Read more closely, however, the book’s spare language and circular structure sustain a far more complicated emotional logic: a study in attachment, ritual, and the slow transposition of care across generations. The prose is elementary by design; beneath that economy, the text stages a life-course elegy that is at once consoling and mildly disquieting.

Form and voice

The author writes in the register of nursery speech—direct, declarative lines and repetition—so the book functions like a lullaby. The recurrent sentence “I’ll love you forever, I’ll like you for always, as long as I’m living my baby you’ll be” performs several jobs: it soothes, it ritualizes love into an incantation, and it marks time as cyclical rather than linear. That cyclical shape is the book’s structural gesture: the narrative begins with a mother’s nightly ritual of carrying and singing to her infant and, in the final pages, inverts the roles so that the grown son, now an adult, visits his aged mother to sing the same song. The refrain binds the opening and closing, giving the story the moral and mnemonic force of a family myth.

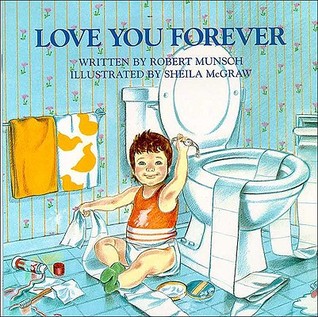

Sheila McGraw’s illustrations are not merely decorative; they are the book’s other half. Her palette—warm domestic tones, carefully observed clutter, and progressively greyer hair—registers a life lived in ordinary settings. Small visual details (a messy house, changing fashions, the child’s evolving toys) quietly provide the temporal markers the text leaves out, a collaboration between word and image that is characteristic of effective picture-book storytelling.

Themes and tensions

The book’s central theme is durable attachment: love as persistence against the erosions of time. But Love You Forever also invites ambivalent readings. The mother’s nightly intrusion into her son’s room—sneaking in to hold him while he sleeps—reads, to some, as tender ritual; to others, as a violation of bodily autonomy and an expression of maternal possessiveness. That ambivalence is productive rather than blemishing: it forces readers to consider where attachment becomes dependence, where ritual gratifies the caregiver as much as it reassures the child.

A second theme is the reversal of dependency. By returning the sequence—adult son comforting the aged mother—Munsch stages caregiving as a life-cycle obligation and a moral recompense. The reversal insists that tenderness is not only a childish need but also a social technology to be returned. In this sense the book is less a sentimental hymn and more a compact meditation on reciprocity and aging: the same lullaby that bound the child to the mother becomes the instrument by which the child, now adult, rebinds himself to the mother as she becomes vulnerable.

Sentiment and criticism

Part of the book’s power is its unabashed sentimentality. Munsch does not code or ironize; he leans fully into emotion. For many readers that directness yields a kind of moral lucidity—love as a stabilizing force in a hectic life. For others, the book’s emotional register can feel manipulative. The refrain’s insistence that love is continuous “as long as I’m living” flirts with existential urgency: the injunction to love is almost a moral imperative to be performed regardless of changing circumstances. Critics have seized on the boundary—between protection and invasion, devotion and control—to argue that the book simplifies the complexities of parent-child relations.

Cultural afterlife

Love You Forever has earned enormous cultural traction; it is read at births and funerals, gifted and anthologized, often cited by adults who report a shiver of recognition. That ubiquity owes much to the book’s ability to function as a portable ritual: the refrain can be sung, memorized, and passed down, converting private family feeling into shared public practice. Its very familiarity, however, raises the risk that readers stop interrogating its assumptions—about gendered caregiving, about consent, about the seamlessness of intergenerational love—and accept a neat, sentimental closure where life is more ambivalent.

As a pedagogical object, Love You Forever is invaluable: short enough for classroom read-alouds, dense enough to prompt discussion about narrative voice, visual storytelling, and ethics of care. As an aesthetic object, it is uneven—most successful when the reader attends to the tension between ritual and intrusion, to the illustrations’ quiet testimony to time’s passage. Those who prize books that refuse complexity in favour of comfort may find it all but perfect; those who want literal realism about boundaries and autonomy will find it wanting.

Read it aloud, but read it twice: once for the lullaby, once with an eye for the fissures beneath the chorus. In that double reading the book reveals its achievement—not the construction of an uncomplicated moral, but the staging of an ordinary paradox: that love, for all its warmth, can be both shelter and constraint, and that the acts of caring which bind us also oblige us to reckon with how—and why—we bind.

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.