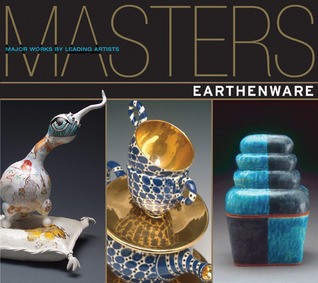

Masters: Earthenware arrives not as a dry handbook but as a museum catalogue written in the idiom of the studio. Curated by Matthias Ostermann and edited by Ray Hemachandra, the volume assembles compact, richly illustrated mini-retrospectives that together argue for earthenware as a lively, experimental, and emotionally capacious medium rather than a mere step on a technical ladder toward stoneware or porcelain. The book’s production — large-format plates, dense plate captions, and voices from the artists themselves — makes it both a practical sourcebook for makers and a persuasive visual argument for critics and collectors.

Formally, the book is organized around roughly thirty-eight artists, each given an eight-page spread that usually presents 12–14 works, accompanied by short statements and technical notes. That tight structure becomes a virtue: it forces each artist into a narrative economy where gesture, motif, and technical variance are immediately legible across a series of objects. As a reader you move quickly from functional vessels to bravely figurative sculpture, and the contrast teaches: earthenware’s very “impermanence” — its low-fire surfaces, porous bodies, and willingness to show repair or crackle — is a site of artistic deliberation rather than deficiency.

What Ostermann’s curatorial hand foregrounds is the dialogic quality of glaze and surface. Many of the book’s strongest spreads are those where glazing is treated narratively: slips become fields, sgraffito becomes script, and painted motifs persist like refrains. The presence of artists’ comments — short, sometimes aphoristic meditations on process and intention — converts what could have been an illustrated inventory into a set of studio portraits. These marginal voices give the book an ethical dimension: the reader is invited to see how intent and accident co-author the finished object.

From a critical standpoint the book performs well as a visual anthology but less well as an extended piece of art-historical argument. The essays and editorial framing are modest; the book never attempts a sustained theoretical account of earthenware’s place in the longer history of ceramics or in contemporary art discourses. For readers seeking interpretive scaffolding — debates about vernacular tradition, postcolonial lineages in ceramic practice, or material feminism — the book provides suggestive examples but not sustained analysis. In other words, it is superb as a panorama of practice and somewhat spare as a vehicle for new scholarship. That limitation is not a failure so much as a statement of intent: this is a collectors’ and makers’ Masters volume, not a monograph in material culture theory. (A reader who moves from this book to a more academic survey will find ample visual prompts for deeper inquiry.)

A final virtue of Masters: Earthenware is its pedagogical usefulness. The arrangement—compact artist profiles, technical notes, and high-quality photography—makes it ideal for studio instructors and advanced students who need exemplars of how concept, surface, and function converge. At the same time, because the photographs and sequences are so carefully edited, the book communicates a curatorial argument about rhythm and variation in ceramics: repetition becomes a method of emphasis; the humble bowl can read as a trope when placed beside a figurative teapot that shares a glaze vocabulary.

Masters: Earthenware is a visually ravishing, practically useful, and a curatorial lucid survey that celebrates earthenware’s contemporary vitality. It may disappoint readers seeking dense theoretical framing, but for anyone interested in the craft, aesthetics, and evolving languages of low-fire ceramics it is an indispensable and inspiring compendium. Recommended for studios, collectors, and undergraduate courses in contemporary craft.

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

This is a thoughtful, balanced, and deeply informed appreciation that treats Masters: Earthenware with both critical rigor and genuine respect. The writing succeeds in honoring the book’s visual richness, curatorial clarity, and pedagogical value while honestly acknowledging the limits of its theoretical ambition. Your analysis makes earthenware feel intellectually alive—an expressive, deliberate medium rather than a technical footnote—and invites readers to see the book as both a studio companion and a persuasive aesthetic statement. An articulate and compelling evaluation that will resonate with makers, educators, and collectors alike.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you

LikeLiked by 1 person