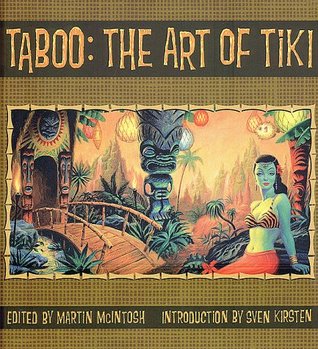

“Taboo: The Art of Tiki” is at once a curatorial flourish and a cultural document: a small, handsome volume that archives a particular late-20th-century fascination with Pacific iconography as refracted through the sensibilities of Lowbrow and pop-surrealist artists. Edited by Martin McIntosh with an introduction by Sven A. Kirsten, and credited with contributions from figures such as Boyd Rice, the book was published by Outré Gallery Press in 1999 as a 96-page softcover that quickly acquired a modest collector’s cachet.

Measured against other survey books of the Tiki revival, “Taboo” is compact but dense: approximately 9 × 10 inches and lavish enough in its visuals to function primarily as an art object rather than a textbook. The volume gathers more than thirty artists working in an aesthetic register that ranges from the cartoonish and camp to the eerily lyrical — names associated with the scene (Mark Ryden, Coop, Pizz von Franco, Robert Williams, Shag, Mary Fleener and others) recur in its pages — so that the book reads as a group show in paper form, a snapshot of a scene that was then consolidating its visual language.

What gives “Taboo” its intellectual curiosity is the friction the editors cultivate between reverence and transgression. The book’s title gestures to sacred prohibitions — the Polynesian concept of taboo — and sets up a dialectic between ritual profundity and the playground of kitsch. Many of the contributed images exploit that tension: tiki heads loom like totemic guardians while simultaneously being bent into jokes, cocktail-bar décor, and noir-ish fantasy. The result is gorgeously ambivalent. The artists treat the tiki idol both as fetishized object and as a blank screen for contemporary anxieties — a symbol onto which questions of masculinity, nostalgia, and suburban escape are projected. The volume therefore functions less as an ethnographic study and more as a cultural symptomology: it documents how a Western popular imaginary recirculates and reimagines the “exotic.” (That framing is not incidental; it is integral to the book’s appeal and, at the same time, the source of its most urgent ethical questions.)

From a formal point of view, the book is careful in its sequencing and reproduction. Pages are arranged so that jumps from dense, painterly spreads to single-image studies feel like a short exhibition: a sequence of visual leitmotifs — masks, shoreline, cocktails, and ritual implements — repeats and mutates. The design amplifies motifs of depth and reflection: reflective surfaces, shadowed reliefs, and a palette that frequently privileges lurid sunset hues and the greened patina of timbers and carved stone. Its compactness is an asset here: the book insists that the reader view the images as a correlated set, prompting comparative readings rather than isolated admiration.

Yet a reviewer trained in the humanities must insist on a complicating caveat. “Taboo” arrives at the height of the Tiki revival in the 1990s, and while it is earnest in documenting contemporary artists’ enchantment with Polynesian forms, it rarely pauses to interrogate the colonial histories that underwrite those forms’ circulation in American popular culture. The book’s essays and introductions (notably the introduction by Kirsten) provide context and enthusiasm, but the volume often assumes the reader’s delight rather than prompting a deeper reckoning with cultural appropriation, missionary histories, and commercialized indigeneity. The absence of a rigorous historical counterweight may be understood as a curatorial choice — the editors prefer immersion over academic distancing — but that same choice makes the book an evocative object for study precisely because of what it omits.

Collectors and historians of late-20th-century visual culture will find “Taboo” rewarding. The book was issued in a relatively small run and has since become a sought-after piece among collectors of Outré Gallery Press titles and Lowbrow ephemera, which accounts for its frequent appearance in specialist used-book markets. Its strength lies in capturing a moment — the moment when a set of artists reclaimed and reinvented mid-century Tiki motifs for a postmodern audience, at once affectionate and mischievous.

“Taboo: The Art of Tiki” is not a definitive history; it is a curated provocation. Read it as you would a focused exhibition catalogue: attend primarily to its images, allow yourself the aesthetic surprise, but keep a critical eye on the cultural logics that make such images legible and desirable. For students of pop art, collectors of Lowbrow material, or scholars interested in the afterlives of “tropical” imaginaries, the book is indispensable as an artefact of the era it records — beautiful, ambivalent, and ripe for further interrogation.

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.