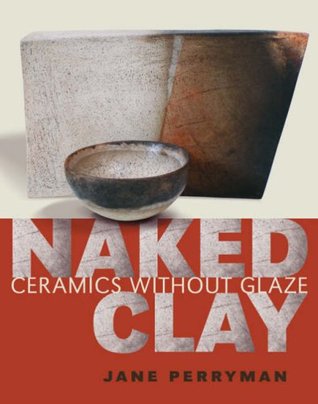

Jane Perryman’s Naked Clay arrives as both manifesto and love letter: a careful, persuasive case for the expressive potency of unglazed ceramics and a sustained meditation on what a surface — left deliberately “bare” — reveals about process, place, and person. The book is at once practical and philosophical, moving between shop-floor particulars (clay bodies, burnishing techniques, firing atmospheres) and broader reflections on material culture, ecology, and aesthetic temperament. Its achievement is not merely to catalogue methods but to show how the absence of glaze becomes a language in itself.

Summary

The book argues that the unglazed vessel — whether burnished terra sigillata, pit-smoked jugs, or the matte, fired surfaces of grogged stoneware — asks us to reorient attention from spectacle to skin. The book is organized loosely into three parts: (1) a primer on materials and techniques that demystifies terms and decisions for makers, (2) a series of essays that place naked clay in historical and cultural perspective, and (3) a suite of case studies — profiles of contemporary makers and projects — that demonstrate how a glazed-less practice intersects with sustainability, ritual, and craft economies.

Strengths

Perryman writes with a craftsman’s eye for detail and a critic’s appetite for meaning. Her technical chapters are quietly brilliant: she refuses the binary of “how-to manual” versus “theory book” and marries precise, tactile instruction (how the clay responds to different burnishing tools; the subtle visual cues of reduction smoke; how particle size alters the feeling of the surface under the thumb) with interpretive commentary about why those particulars matter beyond technique. The effect is pedagogically generous — novices can follow, but the experienced potter will find new ways to name familiar sensations.

Where the book becomes most original is in its account of absence as presence. Perryman treats the unglazed surface not as a lack — as a refusal of ornament — but as an active field that displays process, atmosphere, and time. She shows, for instance, how smoke-marking is not a mere aesthetic accident but an archive of the firing: the path of embers, the breath of the kiln, the humidity of a season. These readings recover an ethics of humility: the maker cedes some control to material and kiln, and in that ceded space the object gains an indexical honesty.

The author also places naked clay within a wide cultural genealogy — from prehistoric cooking pots to vernacular folk-wares, to aspects of the Japanese wabi-sabi sensibility and the turn in contemporary ceramics away from gleaming, perfectionist finishes. Her prose is attentive to metaphor without becoming sentimental: hands are “reading devices,” the kiln a kind of poet’s black box, the clay a slow recorder of human care and environmental conditions.

Context and comparisons

Literarily, Perryman’s voice sits between studio memoir (the reflective, practice-centred writing of potters who write about making) and critical craft studies. Readers who admire Edmund de Waal’s lyric attention to porcelain and objects will find an analogue here, though Perryman’s focus is more processual and less archival. In craft-history terms, she is in conversation with the studio pottery tradition (Leach, Raku practitioners) while explicitly decentering glaze as the locus of value and spectacle. The book can be read as part of a broader recuperation of tactility and modesty in the visual arts — a corrective to glossy, market-driven fetishization of finish.

Limits and critical notes

If there’s one reservation, it is that Naked Clay occasionally privileges poetic argument over critical analysis. In chapters that seek to stake out the political economy of unglazed work — questions about marketability, labor value, and institutional recognition — the book’s observations are sharp but sometimes underdeveloped. It gestures toward important debates (should museums collect unglazed, fragile wares? how do commercial pressures shape aesthetic choices?) but stops short of sustained policy or economic analysis. Similarly, where the book’s most compelling moments arise from the interplay of maker and matter, a few essays rely too heavily on anecdote; a comparative table of clay bodies or firing outcomes would have amplified the book’s usefulness as a classroom text.

Another minor limitation is rhetorical: in her zeal to defend the naked surface, Perryman can read at times as polemical against glazed practice, when a more generative approach might have considered glaze and its absence as complementary strategies on a continuum. Many makers today move fluidly between glazed and unglazed work; acknowledging that hybridity more fully would have deepened rather than diluted her central claim.

Who should read this book

Naked Clay is ambitious in audience: it will reward practicing ceramists (technical chapters + reflective case studies), art-historical readers (the cultural essays), and educators seeking to introduce students to material thinking. Studio managers and conservators will appreciate its clear-eyed notes on durability and handling; artists interested in sustainability and material ethics will find the book’s ecological arguments persuasive. For scholars of contemporary craft, it offers a useful intervention: a theoretically informed but practice-grounded account of how a medium’s “negative” attributes (absence of glaze) can become positive aesthetic and ethical propositions.

Naked Clay is a thoughtful, spirited contribution to contemporary ceramic discourse. It insists, convincingly, that what a surface refuses to do can be as rhetorically potent as what it performs. The book’s rare strength lies in its doubleness — exact about technique, capacious in interpretation — and in its persistent attention to the human hand and the slow intelligence of the kiln. Even where it could push further into economic or institutional critique, Naked Clay succeeds as a practice-minded philosophy of material honesty: an invitation to makers and viewers to read the fired skin of the object as both record and revelation.

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.