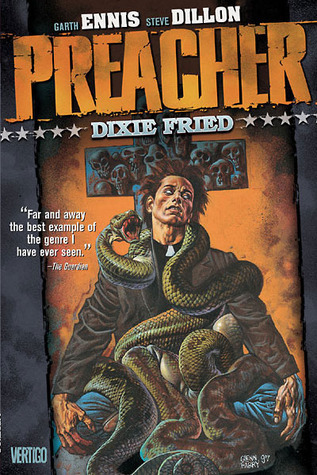

Garth Ennis’s Preacher, Volume 5: Dixie Fried continues the series’ unrelenting descent into the grotesque, the sublime, and the profoundly human. The narrative, illustrated with Steve Dillon’s signature clarity and visceral detail, pushes Jesse Custer, Tulip O’Hare, and Cassidy deeper into their quixotic quest to confront God Himself. In this installment, the trio ventures into the heart of voodoo-laden New Orleans, encountering depravity, redemption, and existential reckoning in equal measure.

At its core, Dixie Fried maintains the thematic backbone of Preacher: an exploration of morality in a world seemingly bereft of divine order. Ennis employs a brutal, sardonic lens to question not just faith but also friendship, loyalty, and the costs of personal mythmaking. The narrative structure oscillates between moments of shocking violence and introspective character development. Cassidy, the hard-drinking, century-old Irish vampire, is given particular depth here as the cracks in his rakish bravado begin to widen. His addiction—both to alcohol and to the bonds of friendship he repeatedly undermines—becomes a focal point, foreshadowing the tragic trajectory of his arc.

The setting of New Orleans serves as an apt metaphor for the novel’s spiritual murkiness. Its fusion of Catholicism and voodoo, its decay and vibrancy, mirror Jesse’s internal conflicts. Ennis uses this backdrop not just for its gothic allure but to reinforce the series’ meditation on belief as a transactional force. The subplot involving the Les Enfants du Sang, a group of wannabe vampires who worship Cassidy, injects a grimly comedic critique of countercultural romanticism. Ennis systematically deconstructs the allure of the monstrous, showing that the real horrors of the world are not supernatural but human—rooted in ego, addiction, and self-deception.

Stylistically, Dixie Fried exemplifies Ennis’s talent for blending high-octane action with deeply philosophical undercurrents. The dialogue remains razor-sharp, often laced with dark humor that tempers the bleakness of the story’s themes. Steve Dillon’s artwork complements this dynamic, his clean lines and expressive character work preventing the story from veering into gratuitous nihilism. His ability to convey nuanced emotional shifts—particularly in Jesse’s increasing disillusionment and Tulip’s growing frustration—grounds the narrative in something profoundly human.

If there is a weakness in Dixie Fried, it lies in its pacing. Some sequences—such as the grotesque humor of the Les Enfants du Sang—risk feeling indulgent, momentarily diverting attention from the novel’s more pressing existential dilemmas. However, these moments also reinforce Ennis’s refusal to let the story become self-serious; absurdity and profundity remain entwined.

Ultimately, Preacher, Volume 5: Dixie Fried is a critical hinge in the series. It deepens the moral complexities of its characters while maintaining the unflinching irreverence that defines Preacher as a whole. Ennis and Dillon continue to wield their narrative as both a battering ram and a scalpel, cutting through the illusions of faith, heroism, and personal salvation. The result is a work that is at once shocking, hilarious, and deeply unsettling—precisely what Preacher was always meant to be.

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.