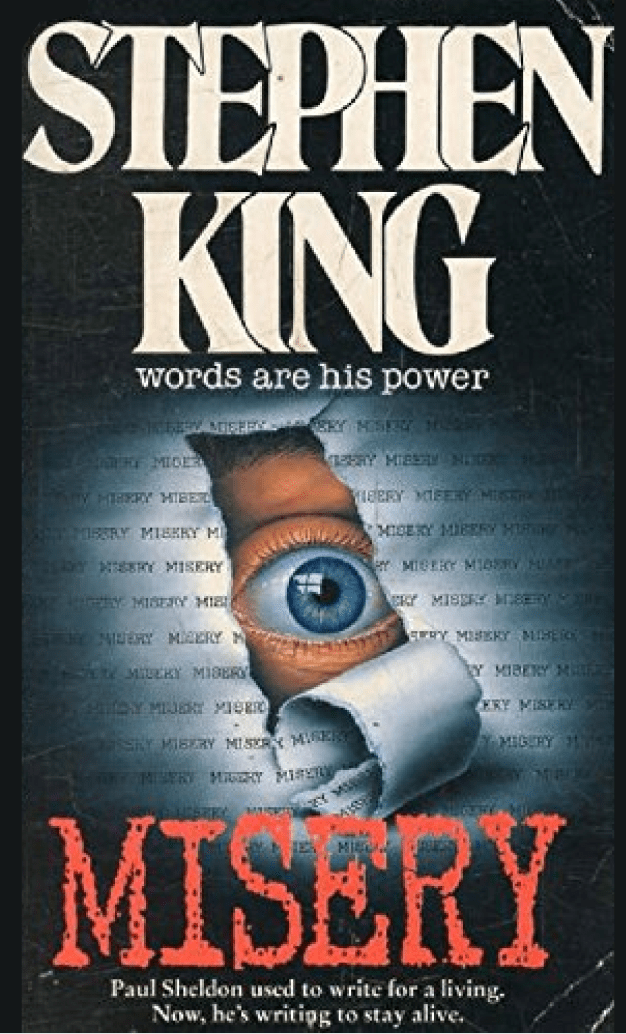

Stephen King’s Misery (1987) is more than a suspenseful tale of literary captivity—it is a deft exploration of obsession, identity, and the precarious line between creator and audience. Framed as a tight, claustrophobic psychological thriller, Misery introduces us to Paul Sheldon, a novelist famed for his nostalgic Regency romance series featuring “Misery Chastain,” and Annie Wilkes, the obsessive fan who rescues him from a near-fatal car wreck—only to imprison him when she discovers he has killed off her beloved heroine.

The Compression of Space and Psyche

King’s choice of the isolated Colorado mountain house as the entire setting transforms the novel into a modern chamber drama. Every creak of the floorboards, every drip of a leaking faucet, becomes portentous, reflecting Paul’s mounting dread. Yet the true claustrophobia is psychological: Annie’s unpredictable kindness—warm meals one moment, bone‑crushing violence the next—suggests that our minds can be more impenetrable prisons than any four walls. In this tight space, King delves into trauma, survival, and the writer’s vulnerability to the visions and voices that haunt his own pages.

The Fan‑Creator Imbrication

Misery stands as one of the most pointed commentaries on the relationship between artist and audience. Annie Wilkes is the archetypal “ideal reader”—she demands what she wants, insisting on sovereign control over Paul’s creative world. Her fan mail becomes love letters that threaten and bind; the once–adoring public now a monstrous presence. King subverts the flattering myth of the benign fan, suggesting that adoration, when unmoored from empathy, can devolve into a coercive power struggle. Paul’s struggle to reclaim his narrative autonomy—both his physical manuscript and, symbolically, his life story—becomes a searing act of creative resistance.

Metafiction and the Price of Authorship

King invites us to consider the “body counts” of his own genre: what the horror author sacrifices in pursuit of his art. Paul’s battered body is not only literal but emblematic of the scars borne by writers who expose themselves on the page. In forcing Paul to retype his novel—word by word—Annie mocks the craft itself, reducing writing to manual labor under duress. Yet King reminds us that storytelling is also an act of resurrection: each typed sentence is Paul’s heartbeat, each revision a step toward reclaiming his agency.

Gender, Power, and the Grotesque

Annie Wilkes is simultaneously nurse and torturer, maternal presence and murderous tyrant. King complicates familiar gender tropes by making his villainess both caregiver and predator, a fusion that unsettles our expectations of female roles. Her grotesque violence—especially the infamous “hobbling” scene—shocks not solely through physical brutality but because it arrives from a figure steeped in domestic nurture. This mingling of tenderness and terror underscores the novel’s exploration of how love, when distorted, can become cruelty.

Legacy and Influence

Misery’s enduring power lies in its fusion of genre thrills with profound questions about creativity and fandom. It has inspired adaptations (most notably the 1990 film brimming with Kathy Bates’s Oscar‑winning portrayal of Annie) and provoked scholarship on fan entitlement and authorial rights. In an era of social media, King’s portrait of the obsessive fan feels eerily prescient: the same instinct that drives us to follow our favorite creators can, unchecked, turn us into captors.

In the end, Misery is not merely about survival against a deranged captor; it is about the resilience of the creative spirit. Paul Sheldon’s battered body and battered manuscript emerge as testaments to the fact that true artistry cannot be caged. Even in the darkest moments, the act of writing—of insisting on one’s own story—remains the most potent form of liberation.

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.