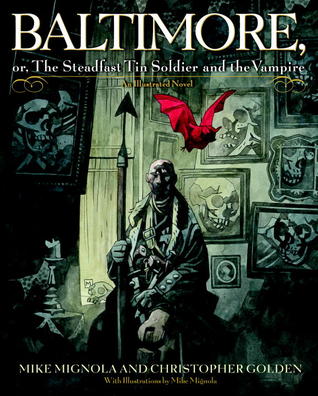

Mike Mignola’s Baltimore, or, The Steadfast Tin Soldier and the Vampire reads like a found object from a ruined twentieth century: a book that is equal parts trench-mud odyssey, moral fable, and Gothic reliquary. Conceived by Mignola and written with Christopher Golden, it was published as an illustrated novel in 2007 and later expanded into a serialized comic-book saga — facts that explain the text’s hybridity: prose that thinks like a graphic narrative, and pictures that puncture prose with chiaroscuro silence.

Summary (brief).

The novel opens in the mud and gas of the Ardennes late in 1914, where Captain Henry Baltimore wounds a vampire and thereby sets off a metaphysical contagion that will upend Europe and his own life. The main action is framed by a hushed, tavern-bound conference: three men wait for Baltimore and tell the stories that led them to believe his monstrous claim. These linked tales—soldier, surgeon, sailor—unspool like fable-episodes and culminate in a confrontation that reframes the war, the vampire, and the nature of heroism itself.

Form and voice.

The authors deliberately collapse literary registers. The prose favours an austere, elegiac register—short, incantatory sentences that leave room for atmosphere rather than analytic excavation. That austerity is precisely the point: the book performs absence. Images and captions interrupt the text with Mignola’s signature black-ink silhouettes and negative-space compositions; the illustrations do not simply decorate but act as pauses, ellipses, and counter-voices. The result is a hybrid reading experience in which narrative meaning is negotiated between what is told and what is shown.

Themes — war, contagion, and the ethics of violence.

At its centre Baltimore is a book about the reverberations of violence. The vampire is not only a supernatural adversary but an index of modern warfare’s moral corrosion: he arrives as plague and metaphor. The novel stages vampirism as both literal infection and ethical contagion — the capacity of violence to reconfigure bodies, households, and nations. By setting the origin in the trenches of World War I, Mignola and Golden insist that monstrosity is both product and mirror of industrial slaughter; the text reads like a short, dark elegy for the illusion that war ennobles.

Intertextual clockwork — Andersen and the tin soldier.

Every chapter begins with a quotation from Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Steadfast Tin Soldier,” and that framing is more than decorative allegory. Andersen’s toy-soldier who remains upright despite loss and dismemberment becomes a foil for Baltimore’s own paradox: steadfastness as both heroism and arrested feeling. The tin heart that Baltimore finally extracts of his chest—literalized, strange, and emblematic—transmutes fairy-tale stoicism into a tragic literalism: to be steadfast may mean to become inhuman. This use of the fairy tale complicates the novel’s moral logic; it questions whether endurance alone is a virtue when endurance costs the human faculties that make moral judgment possible.

Imagery, atmosphere, and limitations.

The artwork is the novel’s strongest argumentative device. His stark, economical lines and blocks of black create a world of silhouettes and hints—just enough detail to ignite the imagination and then to withdraw. Critics have noted how well the book trades on “the simple thrill of a well-told spook story,” and that atmospheric mastery is precisely where the book shines.

That formal strength is also a source of frustration. The book’s commitment to mood sometimes comes at the expense of interiority: Baltimore is an archetype—magnificent, wounded, inexorable—rather than a fully-demonstrated inner life. Secondary figures, too, function as vectors for tale and theme more often than as resolved characters. For readers wanting psychological excavation rather than elegiac myth-making, the novel’s restraint can feel evasive. The later comic serializations will fill some of these lacunae, but the novel itself prefers suggestion to exhaustive explanation.

Legacy and place within Mignola’s oeuvre.

Baltimore sits comfortably alongside Mignola’s Hellboy work in its fusion of folklore, myth, and pulp horror. Its expansion into comics (beginning in 2010) and its continued presence in fans’ conversations mark it as more than a one-off: it is a seed-plot for an outer-verse of stories that mine the same seam of elegiac monstrosity. Its reception—often praised for atmosphere and allegory—reflects a book that performs its argument as aesthetic experience rather than didactic thesis.

Who should read it?

Read Baltimore if you are interested in how genre can be made elegiac—if you want a war story that is also a moral fable and a Gothic tableau. The book rewards readers who appreciate formal interplay between image and text and who are willing to accept suggestiveness and mythic compression in lieu of exhaustive psychological realism. It is not a novel that neatly explains itself; it insists, rather, on dwelling in the uncanny residue left after violence — and on asking whether steadfastness is salvation or perdition. In that insistence it is haunting, ambitious, and finally memorable.

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.