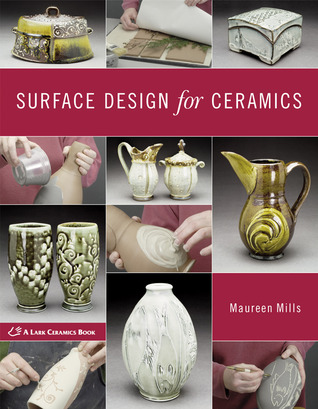

Maureen Mills’s Surface Design for Ceramics reads like a compact manifesto for the small, concentrated art of ornamentation — not a polemic but a pedagogy: a careful, image-rich argument that the surface of a vessel is not mere decoration appended to a form but an active partner in meaning-making. Presented as one of the practical volumes in the Lark “Ceramics” family, the book is modest in length (about 143 pages) yet generous in scope, and it wears its studio-bench provenance plainly: this is a book written by a working potter and teacher for other makers.

Mills’s authority is earned, and she makes no attempt to hide that fact. Her long career as a studio potter and educator — teaching workshops, running a studio with her partner, and serving in ceramics departments — gives the text a lived-in confidence. This is not a theoretical tract imagined in an ivory tower; it is a practicum shaped by the slow, repetitive tests of glaze and kiln, by the weather of the wood-firing shed, and by the particularities of teaching beginners and advanced students alike. That biography matters because it explains the book’s persistent mixture of precise how-to and measured reflection: her examples are the products of experiments in actual firing cycles and classroom critiques.

Structurally the book is admirably pragmatic. Mills moves readers through the chronological opportunities of clay — from wet and leather-hard interventions (faceting, carving, burnishing), through bisque-stage techniques such as terra sigillata and slip decoration, into glazing and the sometimes-volatile alchemy of the kiln, and even to post-firing treatments (decals, lustres, raku). This ordering is more than pedagogical convenience; it is an argument that surface design must be thought temporally, as a sequence of decisions and possibilities that depend upon the material moment of the work. The clear visual sequencing and step photographs create the sense of standing at the bench with the author, a useful stance for makers who learn by watching and doing.

Where the book becomes especially compelling is in it’s treatment of ornament as narrative and memory. It repeatedly frames surface choices in terms of layering, abrasion, and erasure: scars that accumulate into legible pattern; text or calligraphic marks that become indices of process; ash and flame that “write” on form. This language of palimpsest is not merely rhetorical flourish. It reflects a sustained material epistemology in which history, technique, and accident co-author the object’s final rhetoric. Important here is that Mills pairs recipes and technical recipes with design theory and historical examples, so the reader is asked both to learn a technique and to consider its conceptual implications.

Critically, the book’s photographic apparatus is one of its strengths. The plates and step images are neither slickly commercial nor purely documentary; they are detailed and sympathetic to the textures the author describes, allowing subtle differences in brush stroke, slip thickness, or burnishing to be read. For the scholar of craft this is indispensable: the image-as-evidence functions as footnote and demonstration simultaneously. The economy of the book — compact text, rich images, focussed chapters — makes it useful both as a studio reference and as a primer in the aesthetics of surface.

If one seeks an objection, it might be that Mills’s tone occasionally privileges the skilled practitioner’s eye, assuming a tactile literacy that absolute beginners may need more help developing. The book is wonderfully dense with techniques and evocative language, but the novice who has never mixed a slip or fired a kiln might still require supplementary instruction to turn these pages into consistent results. Even so, this feels like a limitation of format rather than of vision: a single concise volume can offer many doors, but not an entire architectural plan for every learner’s journey.

Surface Design for Ceramics is a quietly rigorous, beautifully illustrated handbook that sits at the productive intersection of craft and critical thinking. It is best read with a cup of clay-stained tea at hand, ideally beside a kiln or a workbench. For potters who care about how surface and form converse — and for teachers who need an accessible, image-forward text to frame assignments — Mills’s book is a small, reliable library.

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.