Angelica Pozo’s Making and Installing Handmade Tiles sits at an interesting crossroads: part technical manual, part artist’s manifesto, and part visual essay. The book announces itself as a practical companion for the person at the wheel or the trowel, but its most enduring achievement is how it insists that technique and meaning are inseparable. The book does not present tilework as merely surface decoration, but frames it as a dialogue between hand, material, and place—an argument that will resonate with craftspeople and readers drawn to the material turn in contemporary art and design.

At the level of voice and rhetoric the book is quietly persuasive. Pozo writes with the plain authority of a maker who has spent long hours testing glazes, measuring shrinkage, and reworking joints until they feel right. Yet she also gestures repeatedly toward the poetic: tiles conceived as “small sites” that accumulate memory through feet, light, and use. Those metaphors are not decorative afterthoughts but structural—she repeatedly returns to the idea that the tile’s value accrues not in a single glazed surface but across time and interaction. This fusion of procedural clarity and reflective attention is what lifts the book above a mere how-to.

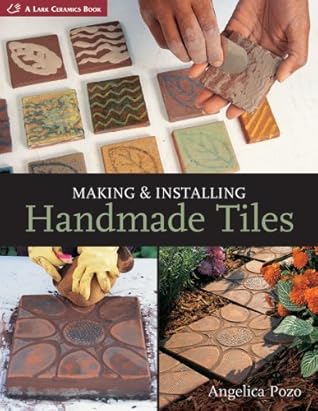

Form and pedagogy are well balanced. Practical sections—preparing clay bodies, forming tiles, firing schedules, mix proportions, substrate preparation, and grouting—are presented with a clarity that will serve both novices and intermediate makers. Illustrations and photographs (tastefully integrated) function as more than examples; they are active companions to the text, showing the grain of hands and the subtle variations that make handmade tile human. Its layout choices—stepwise framing, callouts for common pitfalls, and project templates—are modest but effective teaching devices. The book’s instruction is generous without being didactic: it trusts the reader to learn by doing while providing a scaffold to prevent the most common failures.

Thematically, the strongest move is to reclaim imperfection as an ethical and aesthetic position. Rather than apologizing for irregularities, it names them as evidence of the maker’s touch and as features that animate light, shadow, and pattern. This aesthetic kinship with wabi-sabi sensibilities is never reductionist; Pozo also emphasizes durability, weatherproofing, and proper installation—because a humane aesthetic must also be a functional one. In practice chapters she treats joins, movement allowances, and substrate compatibility with the same care she gives to colour mixing, reminding readers that beauty that does not endure is ultimately self-defeating.

If the book has limitations they are modest and instructive. Readers seeking an exhaustive technical compendium—complete firing curves for every clay, exhaustive chemistry of glazes, or extensive coverage of industrial tile adhesives—may want companion texts. Likewise, while it gestures to historical and cross-cultural precedents, those references are sparing; the book’s comparative history remains a background hum rather than a sustained conversation. For many readers, however, this restraint is a virtue: the book stays focused on realizing craft in contemporary domestic and studio contexts rather than becoming an encyclopedic survey.

Making and Installing Handmade Tiles will be most valuable to makers who want rigorous, empathetic instruction and to designers who wish to reintroduce tactility and time into surface practice. It is an encouragement to work slowly, to respect the stubbornness of materials, and to accept that an installed tile is a social object—it invites touch, ages, and shapes the space it occupies. Pozo’s book is, ultimately, both tool and testament: a field guide for fabrication and a short meditation on why we make things with our hands. For anyone who wants their surfaces to carry both skill and story, this is recommended reading.

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.