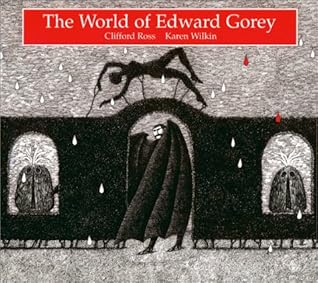

Clifford Ross’s The World of Edward Gorey is less a conventional monograph than an act of tasteful conjuration: a careful, lovingly lit cabinet that sets an uncanny miniature theatre at the center of view. Ross treats Gorey not simply as an illustrator who doodled at the margins of Victorian melodrama, but as a singular authorial intelligence whose shivering formal control — of line, layout, and laconic caption — manufactures a private grammar of disquiet. The book’s chief achievement is to make palpable the very thing the illustrator always made difficult to state plainly: that his works are simultaneously witty, elegiac, and structurally theatrical.

Ross’s appreciation is strongest when he stays with the objects. Gorey’s pen-and-ink drawings, with their tight cross-hatching and obsessive patterning, are shown to be architectural: every chair, every wallpaper motif, every tilted teacup participates in a stage direction. The reproductions (and sequencing) emphasize how Gorey composes a scene as a director would, arranging negative space as insistently as he arranges characters’ poses. In doing so the book reorients casual readers who think of Gorey as a mere maker of macabre jokes; instead, it insists we see the subtle choreography and temporal compression that illustrate his comic gravity.

A recurring strength of the book is its reading of its modes of omission. The narratives are famously fragmentary — a funeral procession cut off mid-gesture, an epigraph that refuses to resolve — and it reveals those gaps not as laziness but as an aesthetic motor: the hush that forces the reader into complicity. Where other critics frame Gorey merely as a Victorian pasticheur or as an enfant terrible with a fetish for morbidity, this tome locates the artist in a lineage of narrative restraint extending from Poe’s suggestive ellipses to Beckett’s paring-down of scene. The result is a persuasive thesis: Gorey’s humor and melancholy originate from the same minimal act of withholding.

The book also excels in attending to Gorey’s language. His captions — droll, blunt, almost juridical — function like epigraphs that refract the visual image. It is alert to the way a single, deadpan sentence can recalibrate an entire picture, converting a domestic interior into an aporia or a pastoral into a crime scene. This attention to the verbal-visual duet is the book’s most valuable corrective to readings that privilege image over text (or vice versa). It treats Gorey’s sentences as stage cues: brief, exact, and indelible.

That said, The World of Edward Gorey is not without limits. The editor’s tone remains emphatically admiring, which yields a book that sometimes misses opportunities for sharper critical distance. Several essays lean toward hagiography; a more dialectical treatment — one that, for example, probes the ethical implications of Gorey’s recurring depictions of childhood, or that situates his aesthetic within late-20th-century consumer and design economies — would have added argumentative depth. Likewise, readers seeking more archival criticism or a sustained histories of critical reception may find the delivery thin: Ross privileges close-looking and curatorial sense over archival excavation or polemical engagement.

Another minor friction arises from an evident desire to map Gorey’s influences. It rightly connects Gorey’s sensibility to Victorian novels, nineteenth-century illustration, and the theatre, but its comparative gestures sometimes flatten differences in tone and politics between source and derivative. A braver comparative stance — one that acknowledged how this artist’s ironic detachment might both inherit and subvert the moral certainties of his forebears — would have sharpened the book’s stakes.

Despite these reservations, the book succeeds as an entrée. It is beautifully produced and genuinely useful for both newcomers and seasoned readers who wish to revisit Gorey with renewed attention. Its reproductions reward slow study, and Ross’s readings, when most focused, illuminate the mechanics behind Gorey’s signature effects: the tilt of a head that signals existential bewilderment, the wallpaper pattern that becomes a metonym for entrapment, the caption whose blandness becomes a blade.

In the end, it offers a convincing account of a maker of polite tragedies — tiny dramas with Victorian habits and twentieth-century disquiet. The World of Edward Gorey will do well on the shelf beside Gorey’s own small volumes: it enhances the pleasure of returning to those pages, and it invites us to watch again how, page by page, Gorey stages the uncanny with the calm of a gentleman director. For readers interested in the craft of picture-text storytelling, or in the peculiar spaces where humour and mourning meet, Ross’s book is a rewarding, if occasionally indulgent, companion.

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.