Caroline Rowland’s The Shopkeeper’s Home: The World’s Best Independent Retailers and Their Stylish Homes reads at first like a beautifully curated cabinet of curiosities — a procession of storefronts and private interiors that insist, by virtue of their arrangement and photography, on a particular kind of attention. But read more closely, and Rowland’s book does something quieter and more interesting: it stages a sustained inquiry into the overlap between commercial mise-en-scène and domestic selfhood, showing how acts of retail curation shape, and are shaped by, the lives of the people who create them.

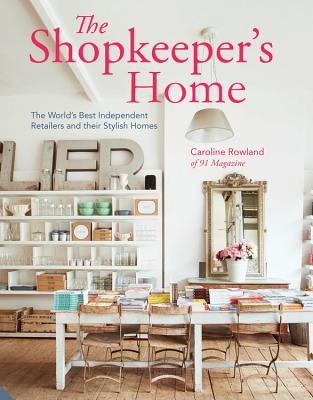

Formally the book is straightforward: across some 224 pages Rowland takes the reader into the shops and homes of more than thirty independent retailers from around the world, pairing richly produced images with concise, well-paced text that privileges observation over argument. The volume’s photographic register — lavish, warm, and tactile — does most of the narrative work; photographers such as Nick Carter and others render surfaces and vignettes with a kind of still-life patience, inviting prolonged looking at materials, light, and the small assemblages that define both shop displays and bedside tables. The visual emphasis is not merely decorative. It functions as ethnography: objects, displays and domestic arrangements are treated as evidence of taste, labor, and biography.

As a scholar of material culture might predict, one of the book’s recurring pleasures is its attention to the ways that public and private styles echo one another. Rowland toys with a comparative logic: the same sensibility that orders a shop’s shelves — restraint, narrative display, an eye for the slightly worn or lovingly restored — often animates the shopkeeper’s living room. The implication here is twofold. On the one hand Rowland tacitly endorses a romantic vision of the independent retailer as artisan-curator, someone whose livelihood is an extension of aesthetic temperament. On the other hand, the book quietly documents the labor and taste economies that make that identity legible, from sourcing and salvaging to the economies of display.

The prose is congenially descriptive rather than polemical. This restraint works in the book’s favour: it allows the material to speak, but it also means the book rarely ventures into sustained critique. For readers interested in the politics of consumption — the tensions between authenticity and branding, the precarious economics of independent retail, or the cultural work performed by “curated” interiors — the book gestures toward these questions without fully interrogating them. In other words, The Shopkeeper’s Home is exemplary as a visual archive of contemporary taste; it is less interested in mapping the larger infrastructures that support or undermine the very shops it celebrates.

Stylistically, it privileges intimacy. The book’s vignettes — a converted gas station that now sells ceramics, a cozy craft shop that doubles as a social hub — emphasize story over exposition, and the result is a collection that feels anecdotal and hospitable. Yet the book’s real accomplishment is the way it stages comparison as a method: by presenting shop and home in tandem, it composes small case studies of how people live with the things they sell, and how retail spaces function as extended living rooms for local communities. These juxtapositions make the book useful not only to interior-design enthusiasts but to anyone studying contemporary urban economies of taste.

If the book has a limitation it is its tendency toward homogenization: the editing favours a particular aesthetic — warm woods, layered textiles, curated clutter — and shops or homes that do not fit that aesthetic receive less attention. A future edition might profit from foregrounding more divergent practices of retailing and dwelling, or by pairing images with short analytical essays that probe issues of scale, labor, and access.

Overall, The Shopkeeper’s Home is a sensorially rich, thoughtfully arranged portrait of a certain strain of independent retail culture. For readers who love interiors books as immersive objects, or scholars who study taste and material culture as lived practice, Rowland offers a generous visual field and a gently suggestive interpretive frame. It is, in short, a book that asks you to look — and, in looking, to imagine the intimate economies that underwrite the objects we buy and the homes we inhabit.

Who should read it: interior-design devotees, cultural historians of consumerism, small-business aficionados, and anyone who enjoys the slow pleasures of a well-photographed book.

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.