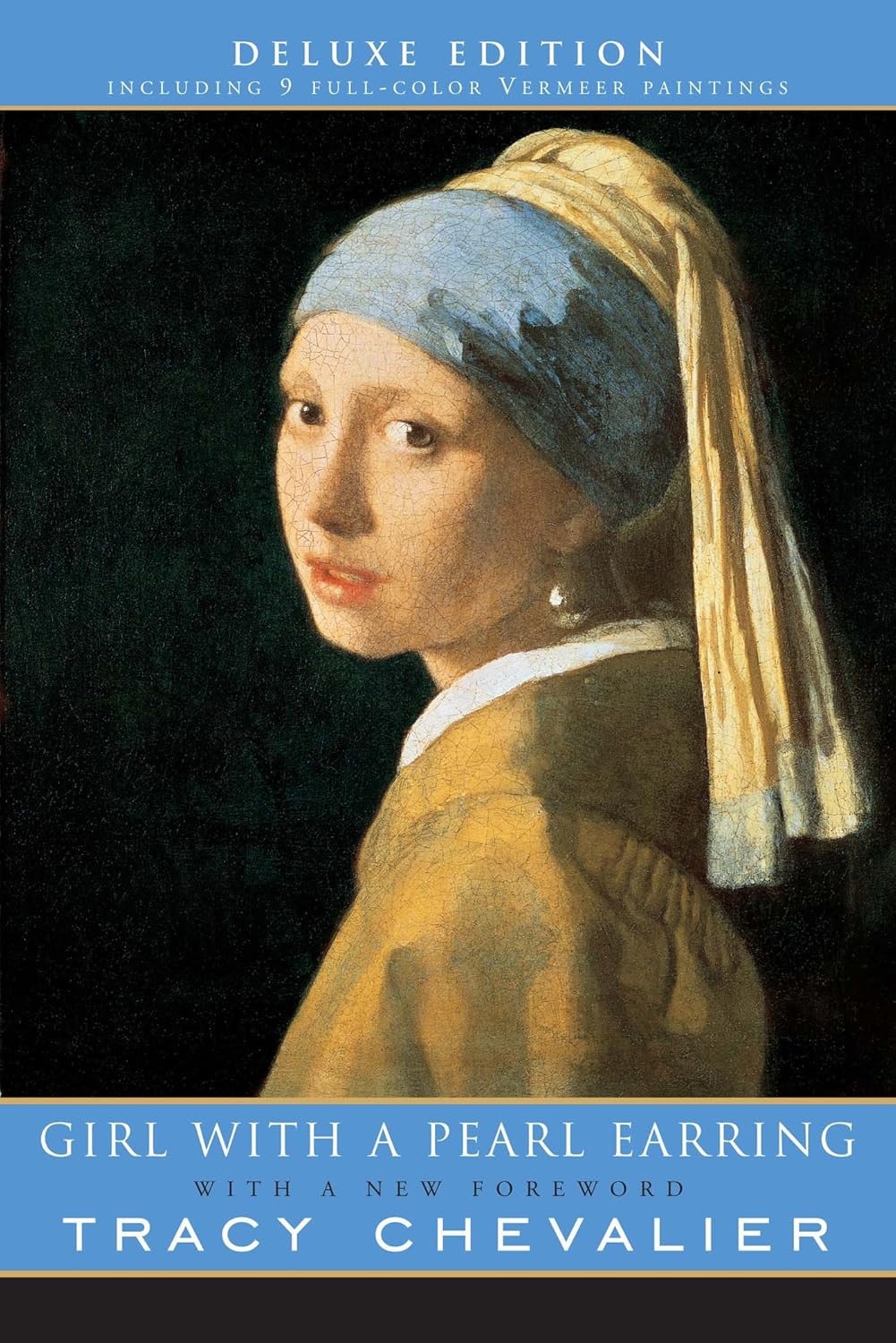

Tracy Chevalier’s Girl with a Pearl Earring is an intricately woven narrative that merges historical fiction with artistic meditation. At its heart, the novel is a quiet yet profound exploration of power, gender, and the transformative capacity of art. Chevalier’s restrained yet evocative prose mirrors the muted palette of Vermeer’s paintings, drawing readers into a 17th-century Delft that feels both tactile and luminous.

Narrative Structure and Historical Authenticity

Chevalier’s decision to narrate the story through the eyes of Griet, a fictional servant in the household of Johannes Vermeer, is both inspired and strategic. Griet’s limited perspective allows readers to experience the enigmatic artist indirectly, preserving his mystique while rendering the domestic intricacies of his world with poignant detail. Chevalier’s research shines here; she reconstructs Vermeer’s Delft with precision, from the cobblestones of its streets to the tensions within its households. The novel’s historical verisimilitude is not heavy-handed but woven seamlessly into the fabric of Griet’s daily life.

Themes of Power and Agency

The novel deftly interrogates the intersection of class, gender, and power. Griet’s role as a servant places her in a precarious social position, making her susceptible to the whims of those above her, from Vermeer’s imperious patron, Van Ruijven, to the artist himself. Yet, Griet’s growing understanding of composition, light, and perspective reveals her burgeoning agency. Her participation in Vermeer’s work—culminating in her role as the model for the titular painting—is both an assertion of her own identity and a capitulation to the objectifying gaze of others. Chevalier captures this duality with a subtle hand, avoiding overt moralization.

Artistic Sensibility and the Gaze

Chevalier’s prose often mirrors the painterly techniques she describes. Like Vermeer, she pays exquisite attention to light and shadow, texture and color. Her descriptions of the studio, with its “pearled light” and “silent shadows,” evoke a sense of reverence for the act of creation. Griet’s awakening to the language of art is one of the novel’s most compelling arcs. However, the novel also critiques the possessive nature of the artistic gaze, especially as it pertains to women. Griet’s transformation into the “girl with a pearl earring” is as much about her own agency as it is about her reduction to an object of beauty and curiosity.

Limitations and Critiques

While the novel’s restraint is often its strength, it can also feel emotionally distant. Griet’s inner world, though meticulously crafted, sometimes lacks the depth that would make her journey fully resonant. Similarly, the enigmatic portrayal of Vermeer, while thematically appropriate, leaves the reader longing for a deeper exploration of his character and motivations. This opacity, however, may be intentional, underscoring the inherent unknowability of genius and the subjective nature of artistic interpretation.

Girl with a Pearl Earring is a masterful meditation on art, power, and the silent voices of history. Chevalier’s prose, like Vermeer’s brushstrokes, achieves a delicate balance between simplicity and complexity, drawing readers into a world where the smallest details—an earring, a brushstroke, a glance—carry profound meaning. While it may not satisfy those seeking grand gestures or sweeping drama, the novel’s quiet brilliance lies in its ability to illuminate the intersections of the personal and the artistic, the seen and the unseen. It is a work that invites contemplation, much like the painti

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.