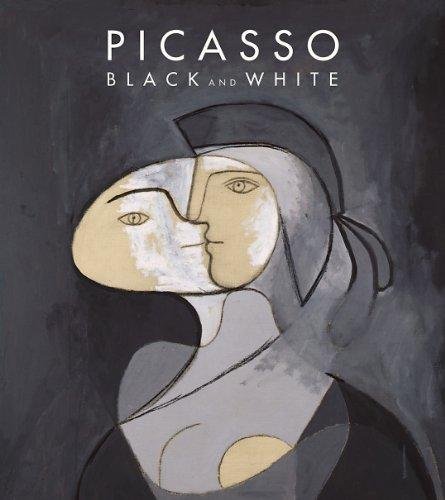

In Picasso: Black and White, edited by Carmen Giménez, the reader is invited to traverse the often-overlooked monochromatic corridor of Pablo Picasso’s immense oeuvre—a space not of limitation, but of liberation. This exquisite volume, published in conjunction with the Guggenheim Museum’s 2012 exhibition, is not merely a visual archive; it is a meditation on the elemental power of light and shadow, line and form, memory and erasure.

Giménez, with her keen curatorial sensibility, orchestrates a compelling narrative through 118 black, white, and grayscale works that span from Picasso’s Blue Period to his late, liberated explorations. By stripping away color—what many might consider essential to Picasso’s expression—this collection reveals something more primal. It exposes the bones of modernism. It renders the mythic artist as a kind of visual poet, composing not with a spectrum but with a stark and distilled language.

From a literary perspective, Picasso’s black and white works function much like a Beckett play or an Eliot poem: pared down, relentlessly precise, and soaked in existential undertone. The absence of color does not signify lack; rather, it introduces a heightened presence, an invitation to see what is usually unseen when chromatic distractions dominate. Much like the spare prose of Hemingway or the negative space in Japanese haiku, these works speak through omission. They are the poetry of what remains.

Consider The Charnel House (1944–45), a painting that resonates with the psychological gravity of a war-ravaged Europe. Here, Picasso’s blacks and whites function not just as visual tools but as moral forces—echoes of Guernica’s cries, distilled to their purest intensity. In Picasso’s hands, white becomes the spectral presence of death; black, its witness.

Giménez’s accompanying essays (along with contributions from scholars like Dore Ashton and Olivier Berggruen) do not merely explain but engage in an almost ekphrastic dialogue with the works. The scholarship is thoughtful without being overbearing, granting the viewer autonomy. In this way, the book itself becomes a literary object—a kind of illuminated manuscript where each image is a stanza and each essay a commentary in the margins.

What’s most striking is how the book—and by extension, the exhibition—reframes Picasso not just as an innovator of form, but as a philosopher of vision. His monochrome works suggest a timelessness akin to myth or archetype. They are less about the moment of creation and more about the universal and eternal—concerns not far removed from the literary canon’s greatest preoccupations.

Picasso: Black and White is not just a catalogue, but an invitation to re-see. For the literary-minded, it reads as a lyric manifesto: a reminder that meaning often emerges more powerfully in constraint than in abundance. Giménez has offered us a prism of grayscale through which Picasso’s genius burns brighter than ever—not in colour, but in clarity.

A masterful curatorial effort that doubles as a philosophical treatise. Picasso: Black and White is essential reading not only for art historians but for any serious student of form, narrative, and the poetics of reduction.

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.