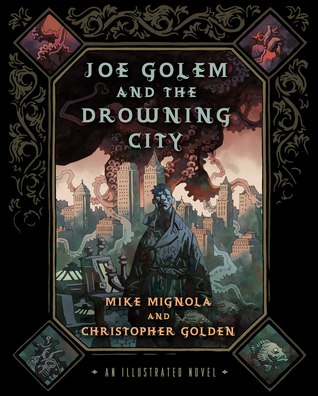

Mike Mignola and Christopher Golden’s Joe Golem and the Drowning City announces itself as many things at once: an illustrated novel, a pastiche of pulp detective fiction, a piece of dark folklore, and a careful exercise in atmosphere. Published as an illustrated novel in 2012, it is a collaborative hybrid in which Mignola’s visual imagination and Golden’s facility with prose reciprocally shape a single mood: elegiac, uncanny, and quietly comic-book-epic.

At the level of premise the book is elegantly simple and therefore potent. In this alternate history, a cataclysm in 1925 leaves Lower Manhattan submerged beneath a tangle of canals and improvised bridges; the “Drowning City” becomes a palimpsest of ruin, refuge, and folklore. Into this half-submerged urban mythscape steps Joe—an almost mythic bodyguard/detective with a blank, square jaw and the riddling skein of a past he does not fully remember—and the shabby, brave Molly McHugh, an adolescent streetwise heroine whose courage and curiosity provide the novel’s moral center. Around them orbit Simon Church (the ageless, sometimes mechanical investigator), Felix Orlov (the stage magician), and a gallery of necromancers, cultists, and ordinary people made strange by loss. The setting—an American Venice of grit, superstition, and rusted machine magic—functions as both stage and character: Mignola and Golden treat the city not as backdrop but as mythic interlocutor.

What the novel most admirably accomplishes is tone. Mignola’s aesthetic—those heavy, clarifying blacks and an economy of line—translates into prose not by imitation but by sympathetic intensity. Golden’s chapters favour crisp, economical sentences and a cadence that leans toward the pulpy: staccato action, droll one-liners, and stretches of melancholic description. The result reads like a vintage serial stripped of nostalgic indulgence; where many “retro” fantasies fall into pastiche’s affectionate mimicry, Joe Golem uses past form to excavate something deeper. The prose and pictures combine to choreograph revelation: illustration punctuates the uncanny, and textual description lingers where the art withdraws.

Thematically, the book works with classic folkloric and existential motifs—identity, authorship of myth, and the ethics of protection—while reframing them in twentieth-century urban terms. Joe himself functions as a displaced golem figure: an artificial protector whose very presence raises questions about agency, memory, and personhood. Yet the novel resists making him an allegorical cipher; his particularity—his mannerisms, his loyalty, his bewilderment—grounds the philosophical motif in humane detail. Molly’s arc, by contrast, is less metaphysical and more reparative: she is the novel’s conscience, insisting upon rescue, truth, and the preservation of stories that might otherwise drown along with the city. Their relationship—guardian and ward, monster and child—is where the book discovers its emotional truths.

Structurally the novel favours momentum over dense exposition, which is both its strength and occasional weakness. Scenes are assembled into a quest whose logic is often associative—dreams and portents bleed into investigation, folklore into procedural beats—so readers seeking tightly wound detective puzzles may find themselves wanting. But this associative architecture is integral to the book’s aesthetic claim: it asks us to read the city as a dream in which myth and municipal neglect co-author catastrophe and redemption. If the plotting occasionally defers satisfaction, it does so in the service of mood and myth-making.

Intertextually the novel wears its influences openly—pulp fiction, Hammer-house Gothic, Lovecraftian hints, and Mignola’s own Hellboy-adjacent weirdness—but it is never derivative. Instead, Mignola and Golden build a hybrid idiom in which the comic-book tradition becomes a vehicle for a kind of American folklore: hard-boiled morality filtered through the occult. The presence of Mignola’s art throughout the book is crucial here; his visuals insist on a particular silhouette of dread and tenderness that prose alone would not achieve. The later expansion of Joe Golem into Dark Horse’s comic adaptations only underlines how well the material straddles mediums—the illustrated novel feels like a node in an extended mythic project rather than a closed artifact.

For the reader who arrives hungry for atmospherics, original monstrous ideas, and a moral center that resists cynicism, Joe Golem and the Drowning City will satisfy richly. It is not, however, a pure exercise in terror: humour and tenderness keep the darkness legible and humane. As a critical caveat, one might say the novel occasionally trades the sharper satisfactions of mystery for the more diffuse pleasures of world-building; some narrative strands are clearly left to be explored later (indeed, the book has been continued and adapted), and readers should expect to follow the authors into the wider “Outerverse” to reap all rewards.

The co-authors have given us a work that sits comfortably between comic art and literary myth-making. It is a novel that believes in the curative power of stories—stories that protect and stories that remember—and it stages that belief in a drowned city whose ruins still sing. For scholars of contemporary weird fiction, of adaptation between image and prose, or of modern myth-making, Joe Golem is a rewarding case study: formally daring, tonally disciplined, and quietly humane.

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

What a beautifully insightful and thoroughly textured reflection on Joe Golem and the Drowning City. Your appreciation of the novel does far more than summarize its premise—it captures its spirit. The way you weave together its hybrid form, its tonal discipline, and its mythic undertones shows a critic’s sensitivity and a storyteller’s instinct.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much, my friend.

LikeLiked by 1 person