Susan Halls’s Ceramics for Beginners: Animals & Figures positions itself at the intersection of pedagogical clarity and sculptural imagination. Aimed squarely at novices, this volume nevertheless aspires—even at the introductory level—to cultivate both technical facility and aesthetic sensibility in its readers. As a literary scholar might probe a text for subtext, narrative arc, and ideological underpinnings, so too can we examine Halls’s manual for its didactic strategies, its aesthetic philosophy, and its potential resonance within a broader discourse on craft and form.

Structural Anatomy and Pedagogical Strategy

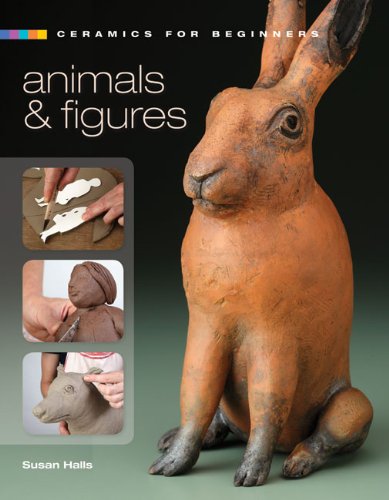

At first glance, Halls’s work adheres to the familiar architecture of a beginners’ craft manual: an opening chapter on materials and tools, followed by progressively complex projects. However, its implicit thesis is that sculpting animals and figures serves as an optimal exercise in understanding organic form, proportion, and narrative expression in clay. The sequence of chapters is deliberately curated to move from elemental forms—such as simple blobs for a “roly-poly” bird—to more ambitious pieces like a reclining canine or a crouching feline. Each chapter begins with a clear list of supplies (clay weight, wire armature, basic hand tools, underglaze pigments) and concludes with “Troubleshooting Tips,” which function almost as a footnote to Halls’s broader pedagogical philosophy: that mistakes in clay should be embraced as part of the learning process.

Halls’s step-by-step instructions are interspersed with high-contrast photographs that play a dual role: they exemplify each stage’s desired outcome and implicitly function as a visual narrative, guiding the learner from block to beast. In this way, the text crafts a pedagogical narrative arc. Where many beginners’ manuals flatten each step into bite-sized instructions, Halls’s layout encourages readers to perceive their work as a developing “text” of clay—each successive mark on the form carrying semiotic weight. The book thus gestures toward a semiotics of surface, inviting readers to consider not merely the “how” but the “why” of each incision or added coil.

Aesthetic Philosophy and Wabi-Sabi Resonances

Although Halls does not explicitly invoke wabi-sabi, her emphasis on organic imperfection aligns with that aesthetic. In the introduction, she writes, “Embrace the quirks—every finger indentation, every slight asymmetry speaks to your personal hand.” Implicit in this declaration is a rejection of mechanical perfection; instead, the beginner is encouraged to allow subtle irregularities to become part of the narrative of each sculpted animal. For instance, in the chapter on constructing a hare, the reader is reminded that “tails can be lop-sided; ears can be uneven”—advice that both frees the beginner from paralysis and situates their work in a lineage of folk tradition, where intentional “flaws” often signify the maker’s intimacy with the material.

Moreover, Halls’s color recommendations—underglaze washes in muted earth tones interspersed with bold accents (for eyes or decorative markings)—suggest a dialectic between restraint and exuberance. This echoes the user’s own affinity for bold colors in painting, while still privileging a subtle, perhaps wabi-sabi–inflected palette in surface decoration. The result is a series of pieces that might simultaneously capture the vibrant energy of a stylized animal and the quiet dignity of a hand-worked form.

Narrative Dimension and Figurative Intent

Beyond technique, Halls repeatedly references the “story” each animal tells. A standing fox, she insists, requires a subtly cocked head to convey alertness; a seated cat demands a gentle hunch in its shoulders to indicate relaxation. In treating posture and gesture as narrative devices, Halls elevates the practise from mere form copying to an exercise in empathy and “character study.” For the literary scholar, this emphasis on story matters: the “figurative” in Halls’s title is not an afterthought but the very locus where technique and narrative converge. Her hermeneutic approach encourages beginners to consider the emotional stance of their clay beings—whether a rabbit looks timid, a dog exudes confidence, or a bird appears mid-song.

At various junctures, Halls inserts short “Reflection Prompts” inviting the learner to annotate their sketchbook with quick notes on posture (“Why is this pig’s trot expressionless?”) or environment (“Imagine where your bear lives”). Though modest in length, these prompts reveal Halls’s underlying belief that ceramics—and particularly figurative ceramics—are as much about human (or animal) psychology as they are about proportion and balance.

Comparative Context and Educational Implications

Within the larger corpus of craft manuals, Ceramics for Beginners: Animals & Figures distinguishes itself by its narrative insistence. If one compares, for instance, to Walter Foster’s earlier volumes (which often emphasize geometry and strict accuracy), Halls’s book reads more like a companion to a student’s sketchbook than a sterile technical guide. This pedagogical choice resonates with contemporary educational theories—such as Universal Design for Learning—by addressing multiple modalities: visual (photographs), kinesthetic (hands-on instruction), and verbal (concise text).

Furthermore, Halls’s integration of “Troubleshooting” alongside aesthetic reflection suggests an inclusive approach. Rather than positioning “mistakes” as failures, she reframes them as opportunities—echoing the constructivist mantra that knowledge is built through iterative, reflective engagement. In doing so, Halls inadvertently positions her manual as an informal introduction to a growth mindset, encouraging beginners to view clay as an active interlocutor, rather than a passive medium.

Strengths and Limitations

A central strength of Halls’s volume is its accessibility: the language is lucid without being condescending, and the layout is spacious—white space around photographs allows the eye to focus on detail. In particular, the sections on constructing wire armatures beneath clay figures are commendable; Halls’s clear line drawings demystify a process often deemed “advanced.” Equally, her encouragement of sketching and preliminary observation fosters an art-historical awareness, inviting readers to study real animals before sculpting.

Yet, one may note certain limitations. Because the book’s scope is deliberately concise, more ambitious projects—such as larger composite tableaux or multi-figure compositions—are reserved for “future volumes.” Those seeking an introduction to narrative scene building in clay might find the focus on individual figures somewhat restrictive. Likewise, readers hoping for an extended discussion on kiln firing strategies or historical context (for example, traditional animal sculpture in various world cultures) may find the treatment cursory. Halls opts for practicality over academic depth, and while this aligns with her stated goal of targeting beginners, it does truncate opportunities for deeper contextualization.

Significance and Audience

Ultimately, Ceramics for Beginners: Animals & Figures stands as a compelling entrée into the world of figurative ceramics. It is at once a technical primer, an aesthetic manifesto, and a gentle introduction to the narrative potential of clay. For educators—particularly those working with mixed-ability classrooms or community workshops—the book provides adaptable lesson frameworks and a reminder of the value of incremental, reflective practice. For self-taught artists or hobbyists drawn to animal forms, it offers a clear path from novice trepidation to modest proficiency, all the while nurturing an imaginative relationship with the material.

From the perspective of a literary-style review, one might say that Halls’s manual possesses a quiet kind of poetics: the very act of coaxing an armature into a fox’s crouch or coaxing a cat’s head into a tilt becomes an act of narrative construction. In keeping with the wabi-sabi spirit that the reader—especially one with a background in art education and an appreciation for imperfection—might value, Halls reminds us that every pinch, every misaligned ear, is a conversation between clay and hand. In this way, the book transcends its “beginner” label to become an invitation: not only to build animals out of clay, but to consider why—and to inhabit, for a moment, the sculptural storyteller’s role.

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.