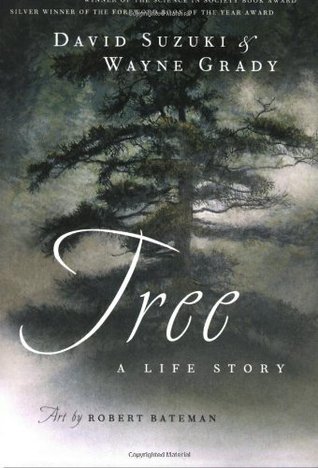

David Suzuki & Wayne Grady’s Tree, A Life Story stages a quiet but insistent argument: to know a tree is to know a world. At once elegy, primer, and manifesto, the book reframes arboreal biography as a mode of ethical attention. Suzuki’s scientific gravitas and Grady’s narrative tact combine to make a book that is neither pure science text nor simple nature poetry; instead it occupies a hybrid space where empirical detail amplifies lyric imagination and where personification becomes a careful instrument of understanding rather than mere ornament.

At the book’s heart is a deceptively simple conceit: the life of a single tree, from germination to maturity and, eventually, to decline. This linear arc—seed, shoot, ring, canopy, senescence—permits the authors to trace biological facts (photosynthesis, mycorrhizal networks, seasonal rhythms) through the lived time of an organism that experiences duration on a scale at odds with human expectations. By zooming in on one life, the narrative offers an ecological parable: the tree is a node in a network, a record of local climate, disturbance, and human intervention. Suzuki provides the empirical scaffolding; Grady furnishes the narrative voice that persuades readers to feel what the scientist documents.

Literarily, the book performs a careful balancing act between anthropomorphism and accuracy. Grady’s use of first- and third-person shifts—sometimes granting the tree quasi-subjective language, sometimes pulling back to an objective catalogue of facts—helps the reader inhabit the tree’s perspective without mistaking metaphor for mechanism. This rhetorical strategy does two important things. First, it enlists sympathy: readers are invited to share in the slow, patient rhythms of arboreal life. Second, it preserves epistemic humility: when language risks overclaiming, Suzuki’s scientific asides return the narrative to measurable processes. The result is an ethical pedagogy—knowledge is shown as the basis for care.

A recurring formal motif—the growth ring—functions for Suzuki and Grady as both literal archive and symbolic memory. Growth rings register droughts, fires, and insect outbreaks; narratively, they offer an image of continuity and rupture. The authors exploit this double role to explore deep time: the tree remembers seasons in a way that human institutions seldom do. This attention to temporal scale is one of the book’s most striking achievements. In an era dominated by accelerated temporality—market quarters, election cycles—the book insists upon an attentiveness calibrated to centuries, not quarters. Such recalibration becomes an implicit critique of modernity’s impatience and extractive logics.

Ecocritical readers will appreciate how Tree navigates the tension between the particular and the systemic. By focusing on a single organism, the book avoids grand abstraction; yet it repeatedly gestures outward, connecting the tree’s fate to logging practices, climate trends, and species interactions. This micro-to-macro movement is rhetorically effective: it demonstrates how policy and economy materialize in the rings beneath our feet. There is a clear political thrust here—Suzuki has never been merely descriptive—and the book articulates a gentle but firm call to stewardship. Importantly, that call is grounded in knowledge rather than in sentimentalism.

If the book has a weakness, it is precisely that occasional didacticism can flatten the aesthetic risk the authors otherwise take. At moments the prose leans toward the explanatory pamphlet, prioritizing conservation exhortation over the stranger, less comfortable ambiguities of ecological thought—questions about non-anthropocentric value, conflicting Indigenous land ethics, or the messy politics of conservation in a capitalist economy. These absences do not fatally undermine the book; they simply mark its limits. Tree is persuasive as a pedagogical text and evocative as a piece of literary-natural history, but it is not an exhaustive treatise on environmental philosophy or a platform for contested land histories.

Pedagogically, however, this limitation becomes a virtue. Tree is admirably suited to classrooms and public audiences precisely because it pairs accessible narrative with reliable science. It can function as an introductory text that opens pathways into more complex debates. For readers who come to environmental thought through feeling—through an emotional recognition of other living times—this book offers vocabulary and context. For those who come seeking data, it provides enough factual ballast to support further inquiry.

Ultimately, Tree, A Life Story succeeds because it refuses a facile opposition between reason and reverence. It models a form of literary naturalism that is intellectually rigorous and ethically charged—an invitation to slow down, read the rings, and let the human imagination be stretched by the patience of other lives. For anyone interested in environmental literature, natural history, or the moral work of knowledge, Suzuki and Grady’s book offers a lucid, humane, and ultimately persuasive argument for seeing the world as a community of lives rather than as a storehouse of resources.

Discover more from The New Renaissance Mindset

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.